|

Reclaiming Clement's Letter to Theodoros – An Examination of Carlson’s Handwriting Analysis

1.1 Introduction

In his book The Gospel Hoax: Morton Smith's Invention of Secret Mark (2005), Stephen C. Carlson sets out to prove that the letter which Morton Smith claimed to have found in the Mar Saba monastery in 1958, and in which the early church father Clement of Alexandria refers to a mystic (secret) and expanded gospel of Mark, actually is a forgery made by Morton Smith himself. Since Carlson released his book in 2005, most of his observations and arguments have been analyzed, mainly by Scott G. Brown; in some instances these have been fully refuted and in others, alternative and often more probable interpretations have been presented.

The one argument presented by Carlson which has most impressed his readers is his handwriting analysis. He claims that the letter shows signs of being written deliberately and much slower than what one would expect for a rapid cursive hand. The signs of the work being a forgery are 1) “Blunt ends at the beginnings and ends of the lines [of the letters, which] indicate that the strokes were written so slowly that the pen had come to a complete stop at the ends of the strokes”; 2) unexpected pen lifts; 3) the “forger’s tremor,” meaning a shaky line quality resulting from drawing letters instead of writing them naturally; 4) retouching of the letters; and 5) inconsistency in the writing. Although Walter M. Shandruk in a blog post named Carlson’s Handwriting Analysis on Secret Mark has made some interesting observations, Carlson’s arguments have to my knowledge never been thoroughly examined.

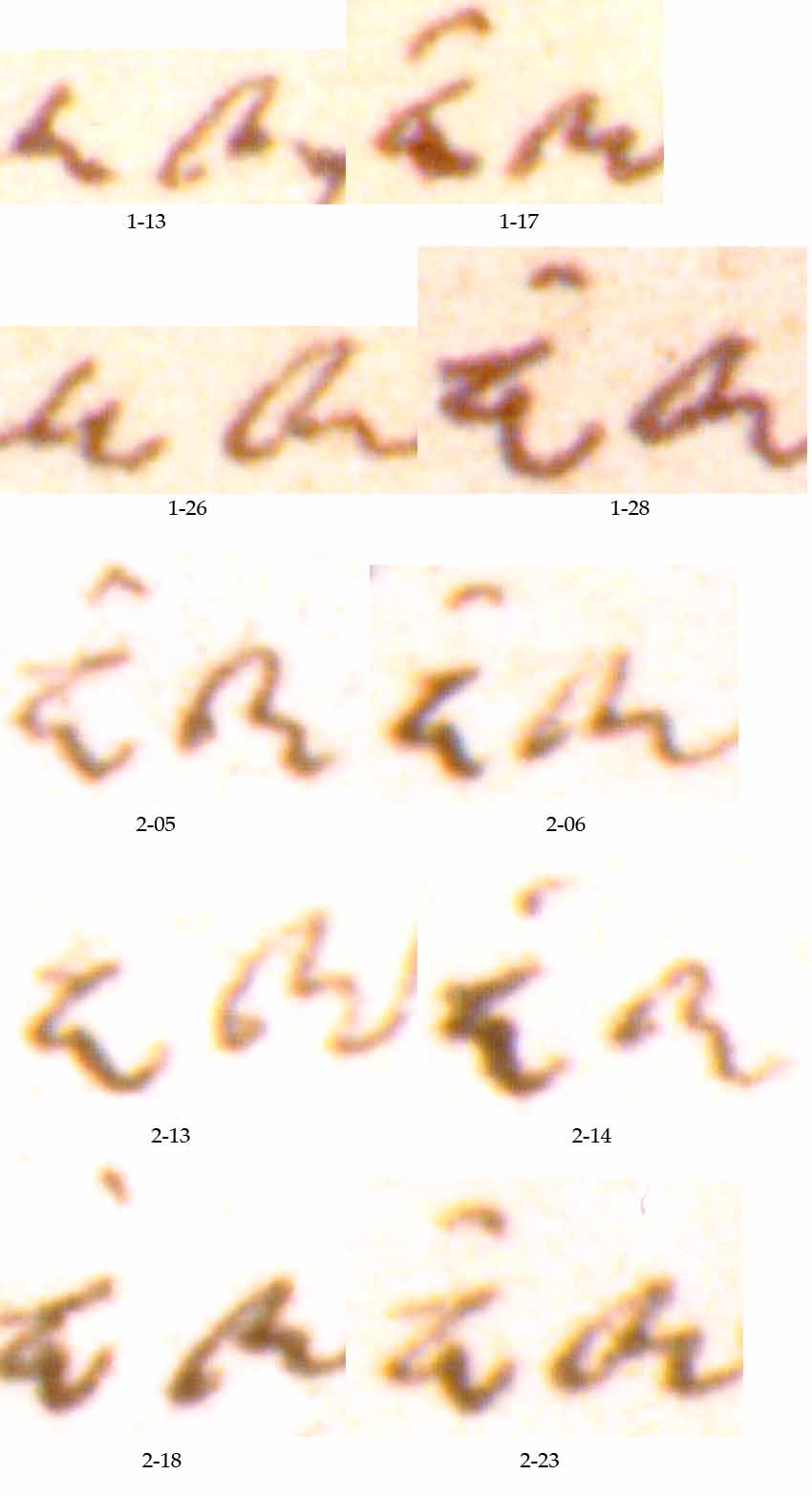

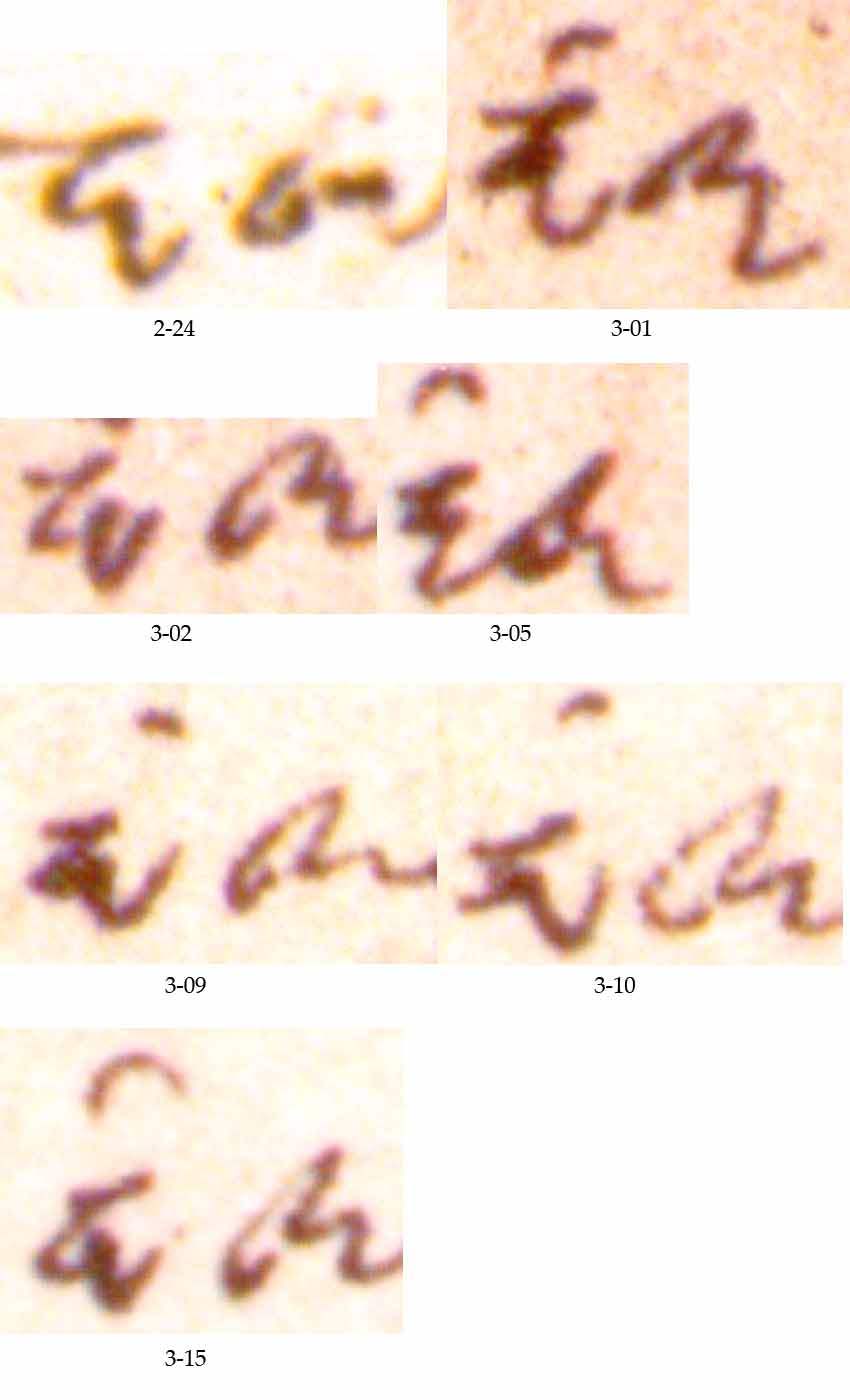

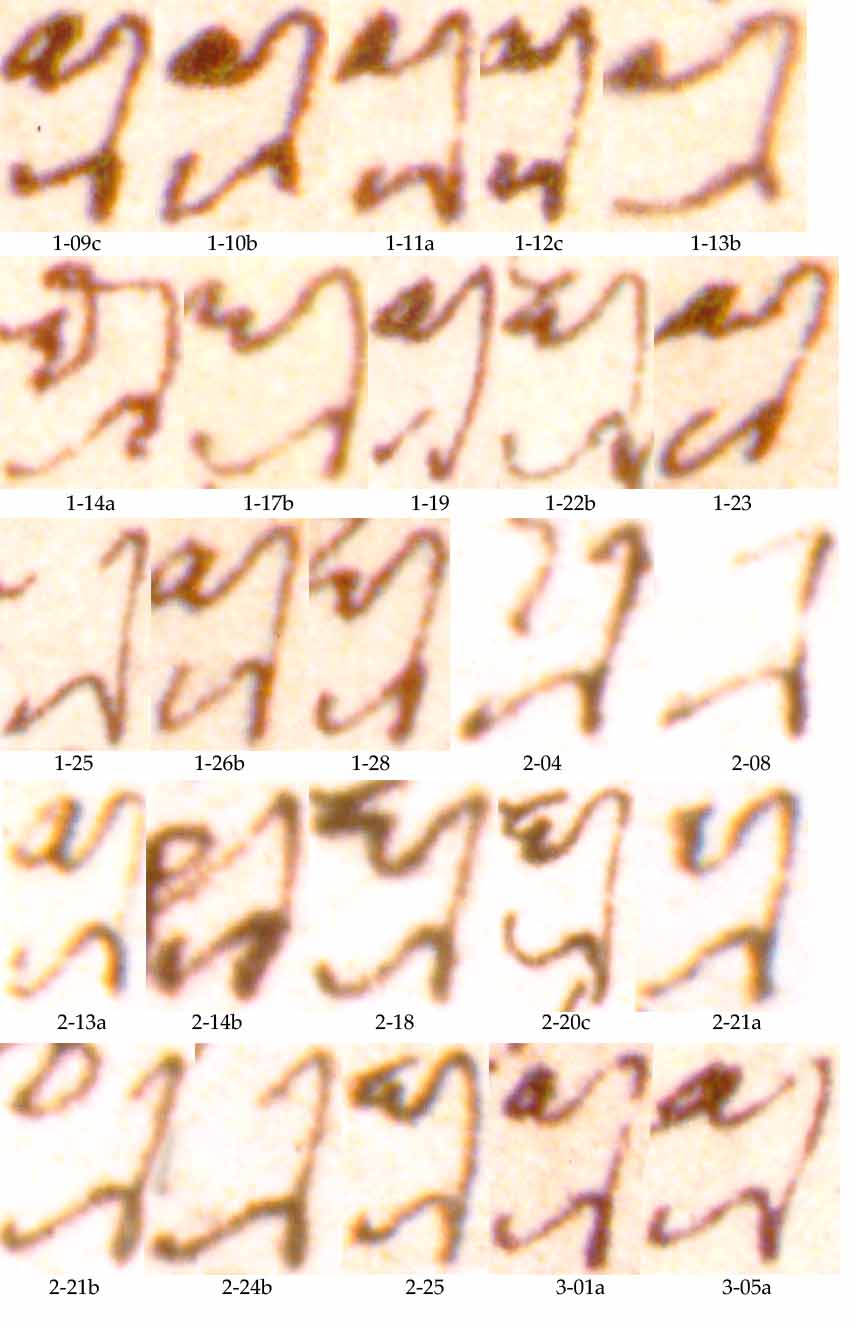

In his handwriting analysis chapter,[1] Carlson gives many examples of what he sees as signs of forgery. These examples however are restricted to only five pages (pp. 27–31) where only a few examples are illustrated with enlarged images and the rest are illustrated in actual size reproductions of lines of text where the individual letters are too small to be evaluated. In this article I will investigate every example given by Carlson. In order to do so, I have used 1200 dpi scans of the Letter to Theodoros (the Mar Saba Letter) from colour photographs taken by Archimandrite Kallistos Dourvas.[2]

This examination will for the time being be restricted to internal comparisons, since I yet have no access to any other eighteenth-century manuscripts. I will though hopefully obtain permission to publish material for comparison, among other things MS 22 from Mar Saba. In every instance, I will first give a brief description of Carlson’s example, accompanied by the actual image which Carlson refers to. Thereafter I will present other instances (often all other examples in the entire text) where this particular letter or combination of letters occur. The readers will then hopefully be able to judge for themselves. However, I will also as a layman present my own observations and my own conclusions based only on what I see and what I think is a reasonable interpretation.

It should be noted that Carlson gives only what he sees as the most obvious examples, and only from a few lines in the document. His examination is restricted to the lines 1, 4 and 7 on page 1 (which has 28 lines), lines 18 and 26 on page 2 (which has 26 lines) and line 18 on page 3 (which has 18 lines). Carlson claims indirectly that there are many more examples which he did not present in the other lines of the manuscript, but wants to show that the writing improved and became more fluid as the scribe became more confident. My evaluation will be restricted only to those examples which he actually presents.

1.2 Preliminary Comments

The letter is written on three formerly blank pages inside a book, Isaac Vossius’ 1646 edition of Epistolae genuinae S. Ignatii martyris. In 1958, at his visit at the Mar Saba monastery, Morton Smith took black and white photographs of the pages, and these were reproduced in his 1973 book Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark. It was these halftone reproductions in Smith’s book which Carlson was working from. I have instead used 1200 dpi scans made directly from the colour photographs that the librarian Archimandrite Kallistos Dourvas took of the pages in the late 70s and which were published in The Fourth R, 13:5 (2000) by Charles Hedrick and Nikolaos Olympiou in the article “Secret Mark: New Photographs, New Witnesses”. Considering the vast amount of comparison examples in this article, I have seldom stated from which word the letters or combination of letters belong. I have only given the page and the line. Each comparative image has been given a number, for example 2-09. This convention means that this particular letter belongs to line 9 of page 2 based on the photos taken from the book. If there were more than one example in one particular line, letters, beginning with a, were added at the end, i.e. 2-09a, 2-09b and so on.

2. Blunt ends at the beginnings and ends of the lines

2.1 Blunt ends

”Blunt ends at the beginnings and ends of the lines indicate that the strokes

were written so slowly that the pen had come to a

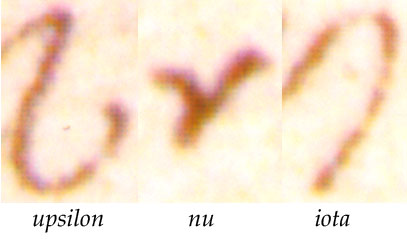

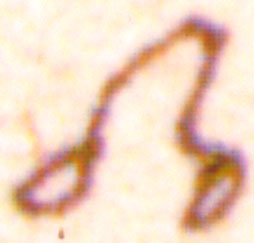

Almost all examples of blunt ends presented by Carlson are those that according to him also have ink blobs. Only 3 examples of just blunt ends are given; “for example, at the end of the first upsilon in ἐλευθέρους, and at the nu and the second iota in εἶναι”. These three letters are presented to the right to illustrate what Carlson means by “blunt ends”. No comparison material is presented as it will be restricted to those examples where Carlson sees “ink blobs”.

2.2

The sign of the cross

Carlson writes that when the pen stops it gives blunt ends:

”In Theodore, the pen had been on the paper even longer than that, since the ink continued to spread into the paper, leaving an ink blob.”

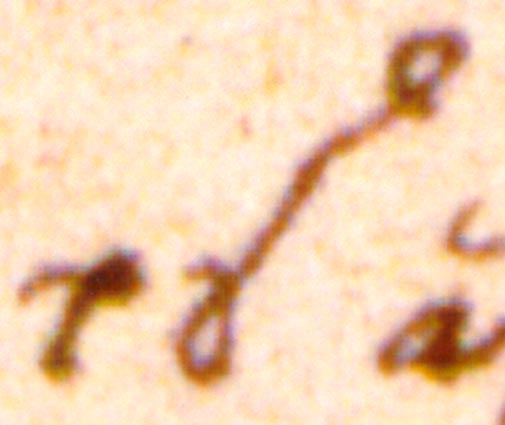

First of all there is “the sign of the cross” at the beginning of the first line on the first page. This “cross” occurs only on one occasion and there is consequently no other “crosses” to compare it with. It can however be compared with other letters which will be presented further down, specifically the short tau below.

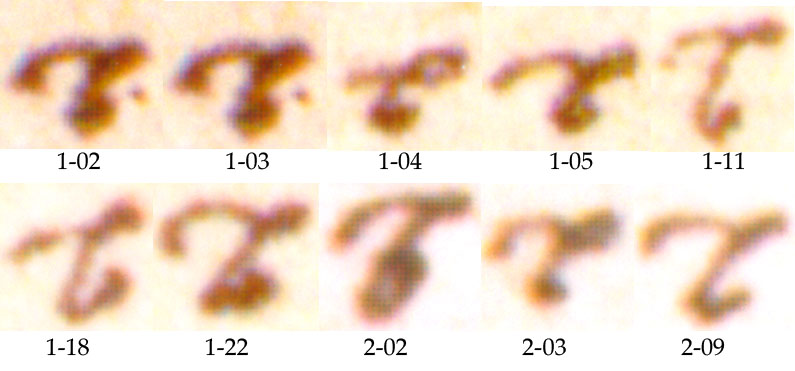

2.3 The tau in τῶν

Carlson continues:

“Many letters of this line [1.1] of Theodore feature the blunt ends that evidence the writer’s hesitation at the beginnings and ends of strokes, and the most egregious hesitations that resulted in ink blobs include the tau in τῶν”

However,

there is obviously not an ink blob at the lower end of this tau. Instead

the vertical line seems to have a hook to the right, in the same way as the

small

Carlson refers to another ink blob in a tau in the first τοῦ in line 1. He writes:

Carlson is correct in noting that this is the only exception where a short tau is used when a tall should have been used. Carlson seems to suggest that this is an indication of forgery, since the scribe was uncertain at the beginning and became more confident as work proceeded. This is, as far as I can see, an unproven assumption. If the scribe lived in the eighteenth century and was copying an older original, it could very well be an uncial manuscript and the scribe just happened to use the “wrong” tau when he transformed from uncials to minuscules. More on that later!

If, however, we are witnessing a forgery, the counterfeiter would have needed to first create the text; both invent it and write it down. This master-text would reasonably be made in eighteenth century Greek handwriting which the counterfeiter should have proofread before he copied it into the endleaves of the book. The faults included would therefore first and foremost be the ones the forger wanted to be included. The forger would also normally be more careful to use the correct letters in the beginning and the errors would be more likely to appear at the end, when mental fatigue would produce more errors. If a forger took a long break, this I think would be seen as a distinct change in the writing when the work resumed. I therefore suggest that all three pages were written after one another without any break. It therefore seems more likely that someone in the eighteenth century copying an uncial manuscript made an error at the beginning than that a counterfeiter copying his own prepared forgery made an error at this point.

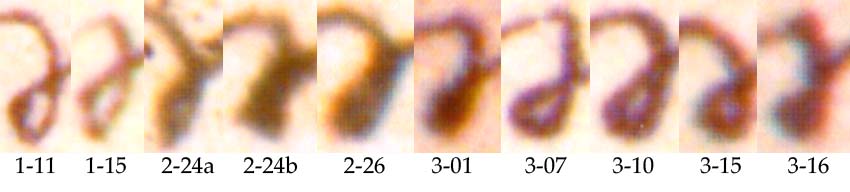

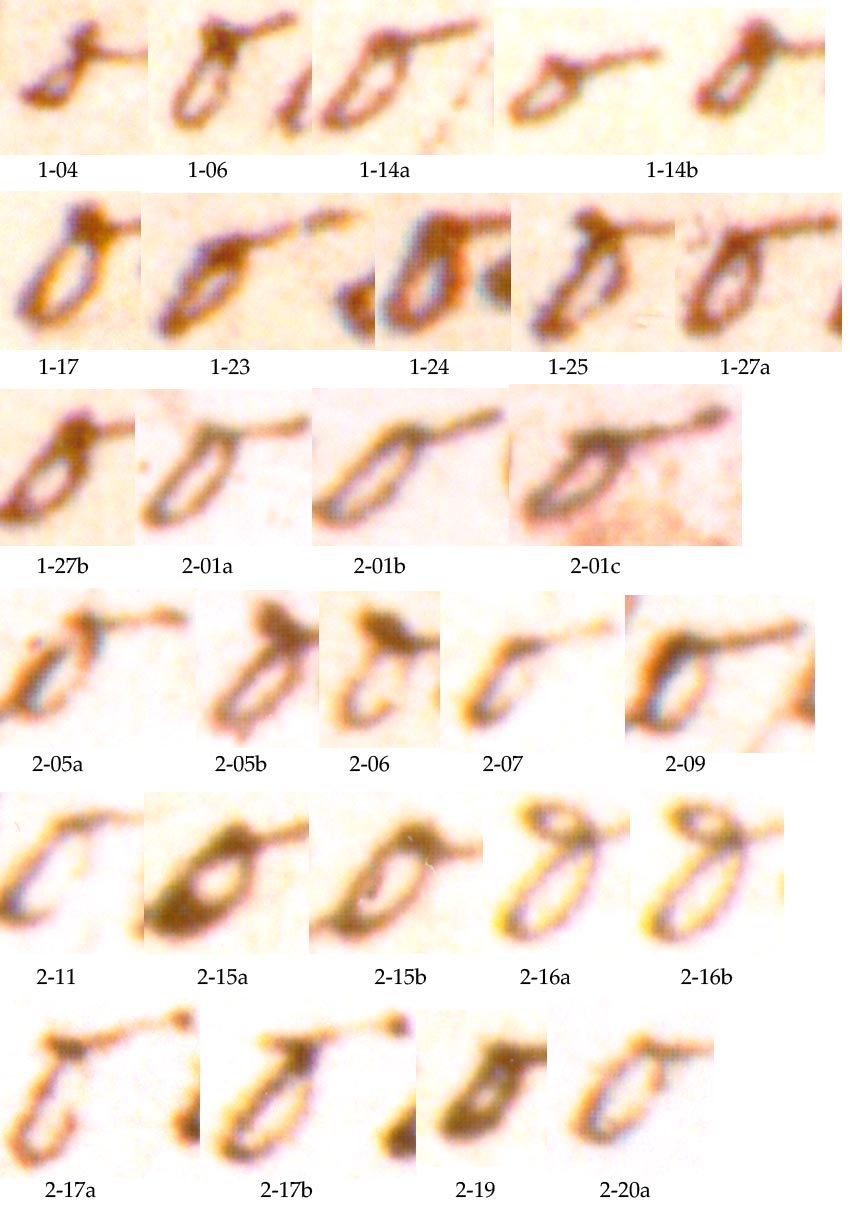

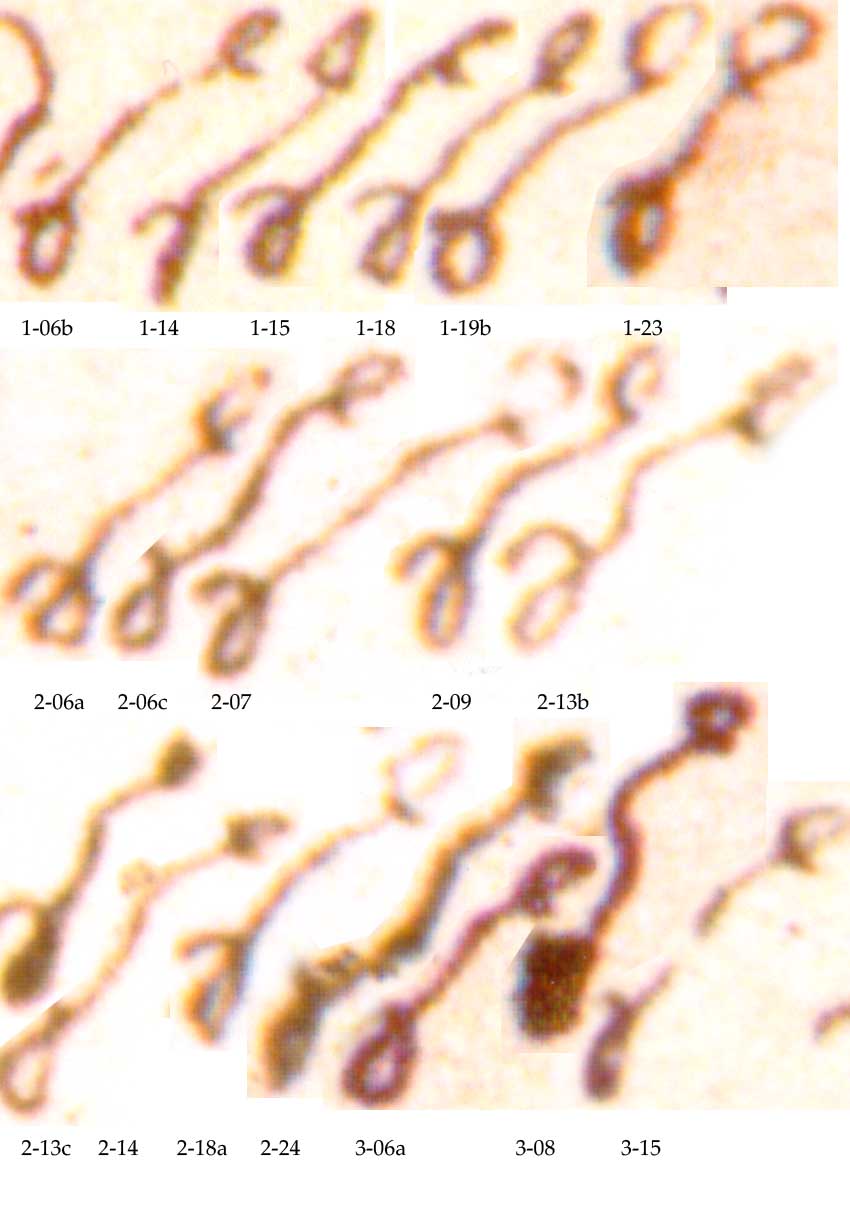

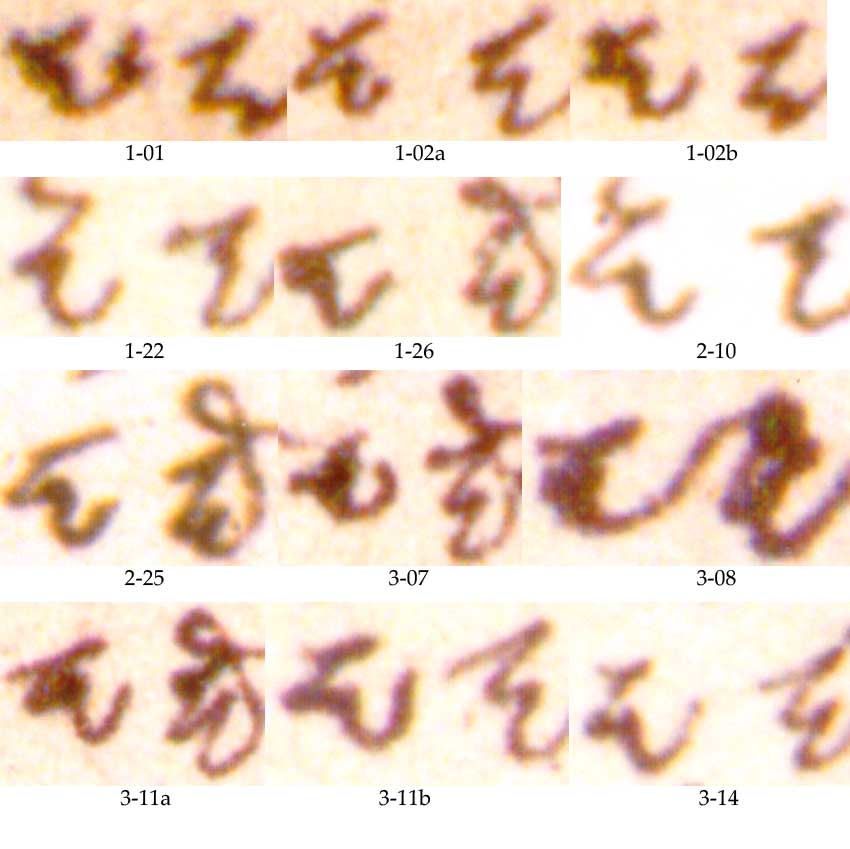

I am unable to determine where the actual ink blob is; whether Carlson sees it just under the horizontal stroke in the turning at the right top or in the small hook at the very bottom, or maybe in both places. I provide all other small taus in the Mar Saba Letter.

As clearly can be seen, there is a hook at the bottom of every tau and there are also “ink blobs” at the hooks and in those taus where the turning at the right top is narrow. Carlson also refers to an ink blob in “the tau of τῶν” in the fourth line of page 1, the one presented as 1-04 above. I cannot see in what way this tau would differ from the other taus.

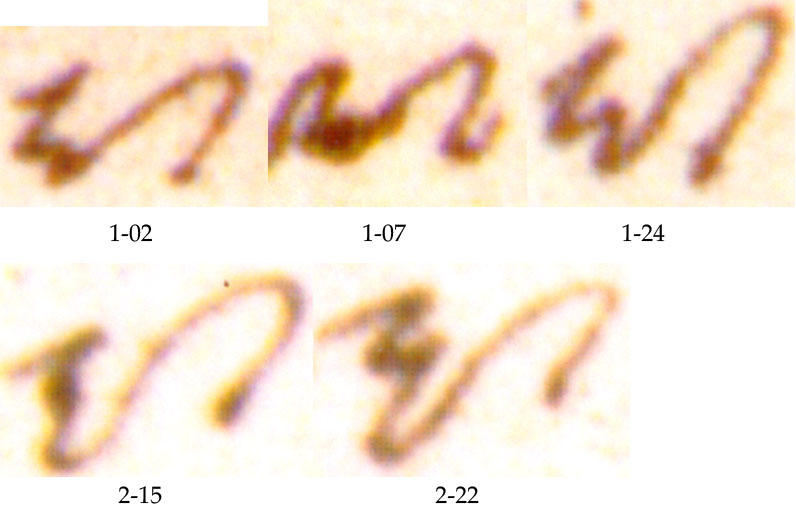

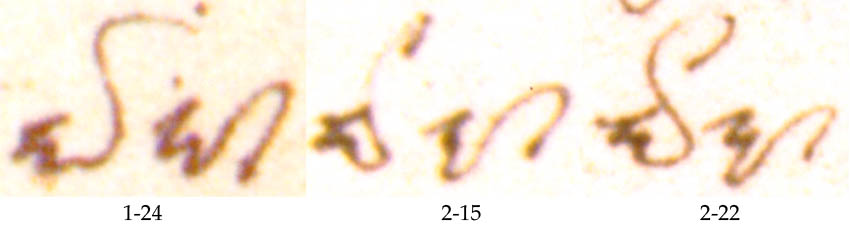

2.4 The iota in ἐπιστολῶν

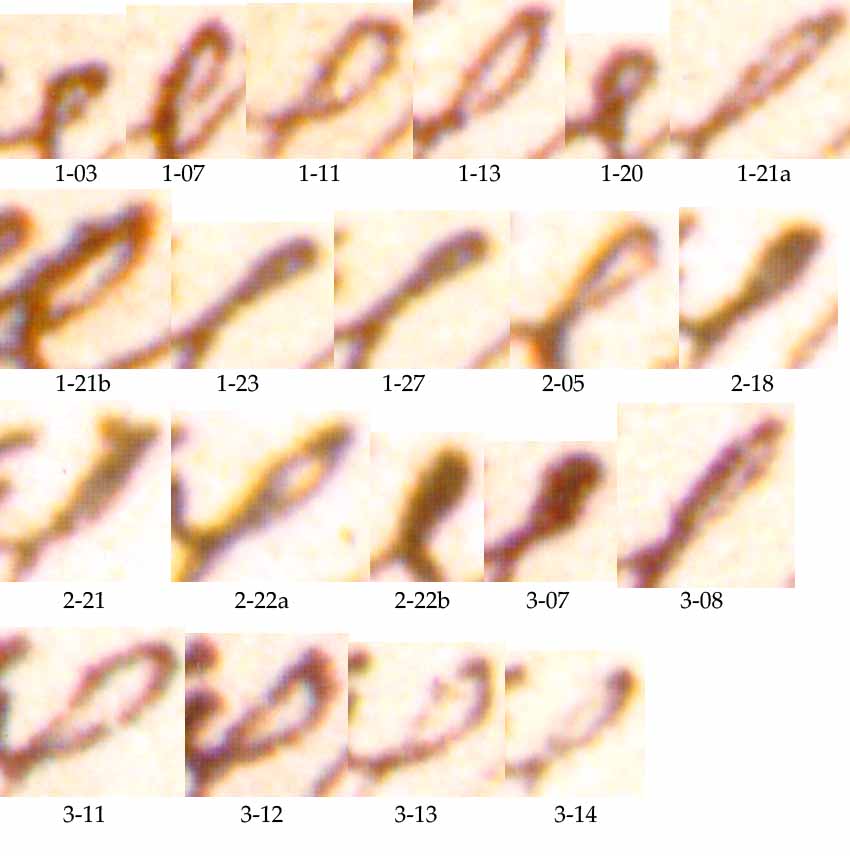

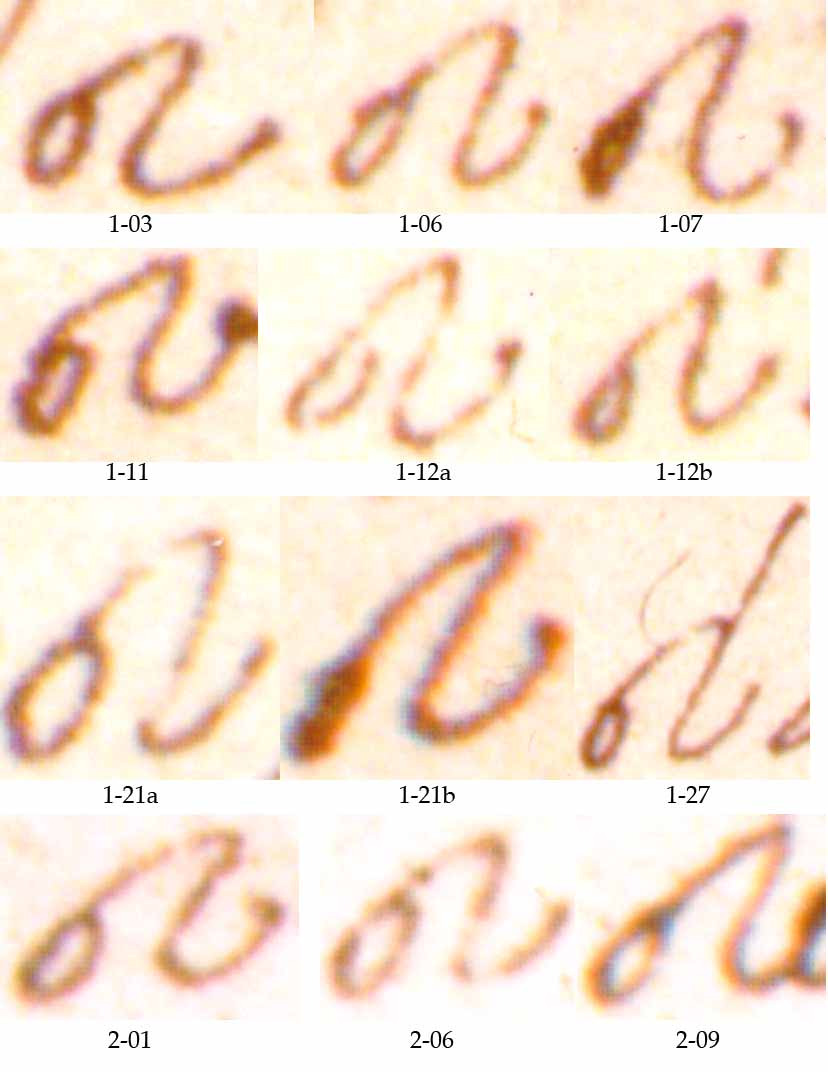

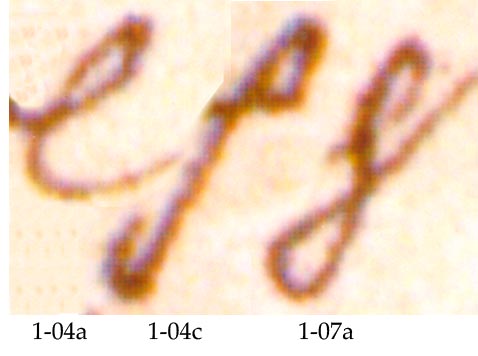

The next example Carlson provides is “the iota in ἐπιστολῶν” in line 1 of page 1. Here is Carlson’s example with the πι cropped from ἐπιστολῶν. The iota however seems to have a hook to the left and there is no ink blob as far as I can see. I provide the five instances apart from this one where the πι-combination occurs.

In four of these five

examples

the iota ends with a blob. Also in 1-07

there seems to be a blob at the bottom before the line turns upwards to the

right. In Carlson’s example there is a hook to the left – in 1-07 a hook to the

right. Otherwise there is no hook apart from possibly 1-24 where there could be

a small hook to the left.

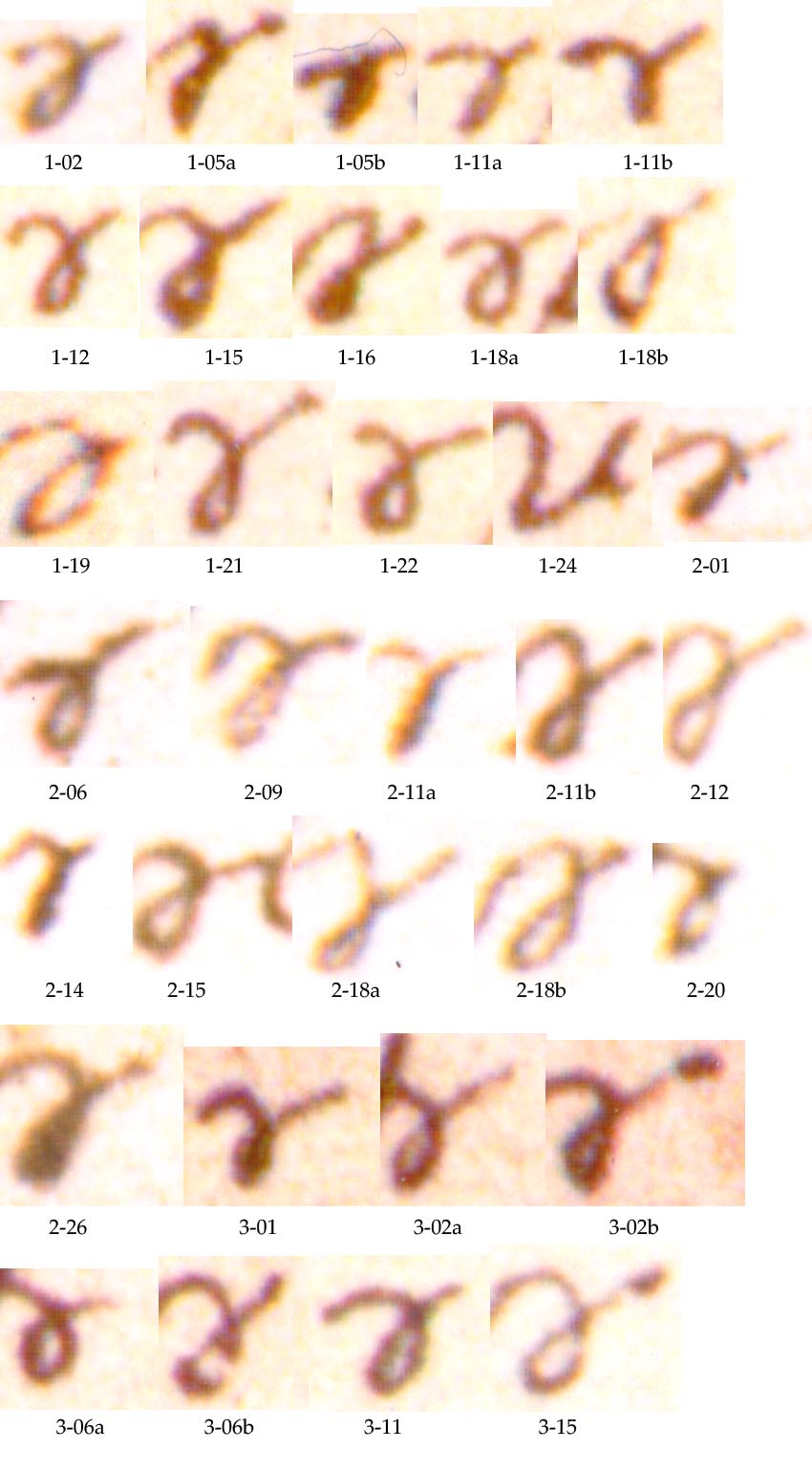

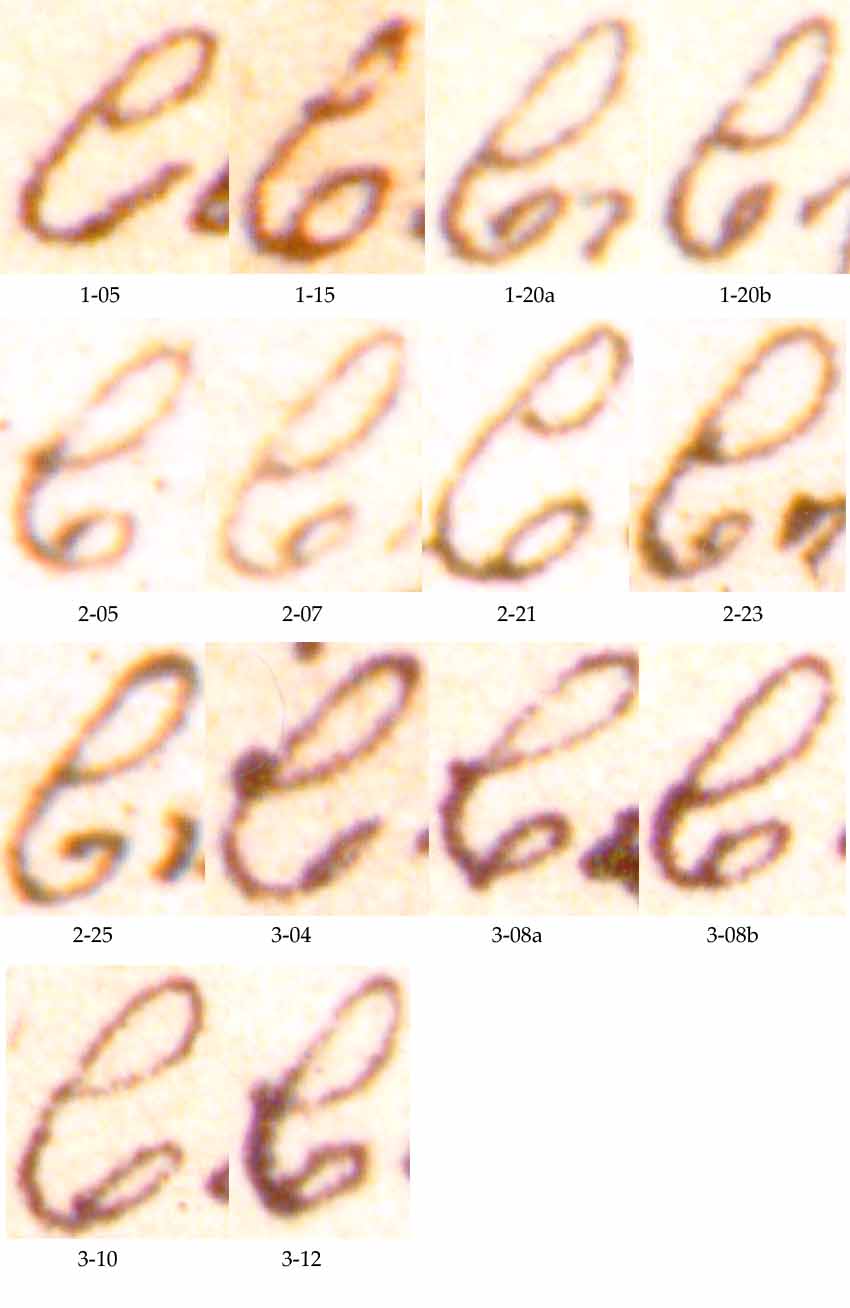

2.5 The omicron-upsilon ligature in ἁγιωτάτου

The next example is also in line 1 of page 1 in the word ἁγιωτάτου. Carlson sees a blob in “the omicron-upsilon ligature at the end of ἁγιωτάτου”. The omicron-upsilon ligature Carlson refers to is presented to the right. There are many omicron-upsilon ligatures, and below are all that lack apostrophes and also which are not connected, either before, after, or both. For a more high-resolution image, click here!

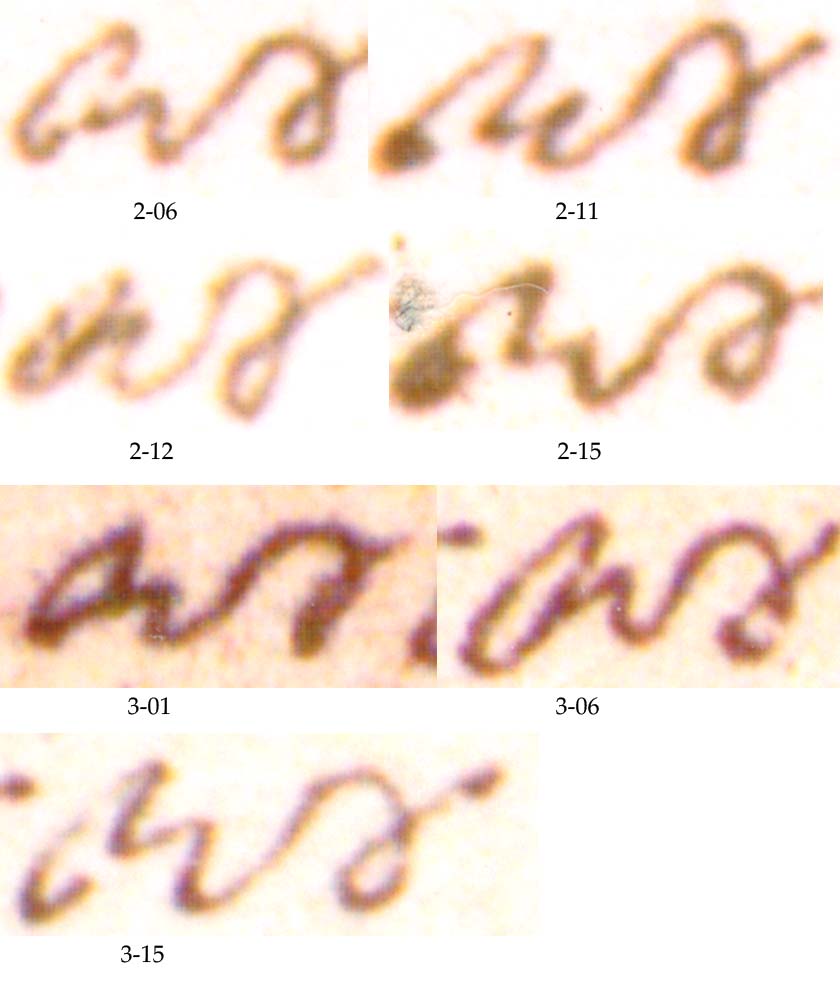

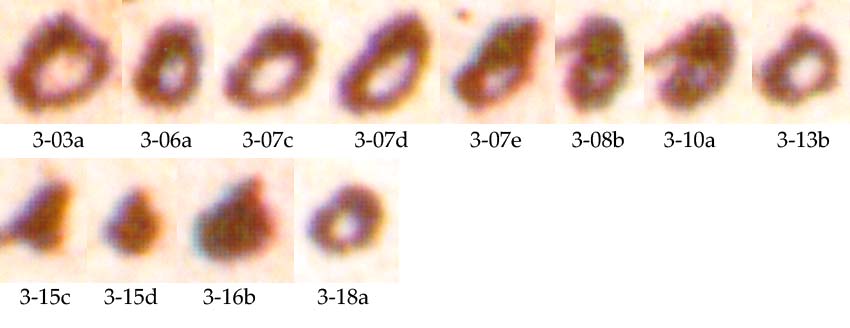

As is clearly seen the images show what according to Carlson’s standard must be regarded as “blobs” in at least 1-05a, 1-16, 1-18b, 1-21, 2-09, 2-11b, 2-12, 2-15, 2-18b, 2-26, 3-02b, 3-06b and 3-15. The most reasonable conclusion to me seems to be that the scribe often ended the omicron-upsilon ligature rather abruptly. Interestingly though, expressed as percentage, there are more blobs at the end of the manuscript than at the beginning. In page 1, blobs can be seen in 1-05a 1-16, 1-18b and 1-21, and of course also in Carlson’s example, i.e. 5/16 ≈ 0,31 (31%), whereas in page 3 they are present in 3-02b, 3-06b and 3-15, i.e. 3/7 ≈ 0,43 (43%).

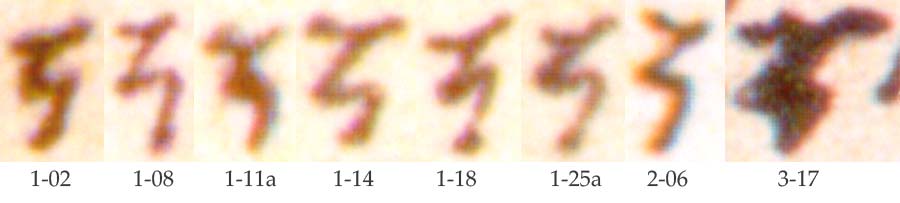

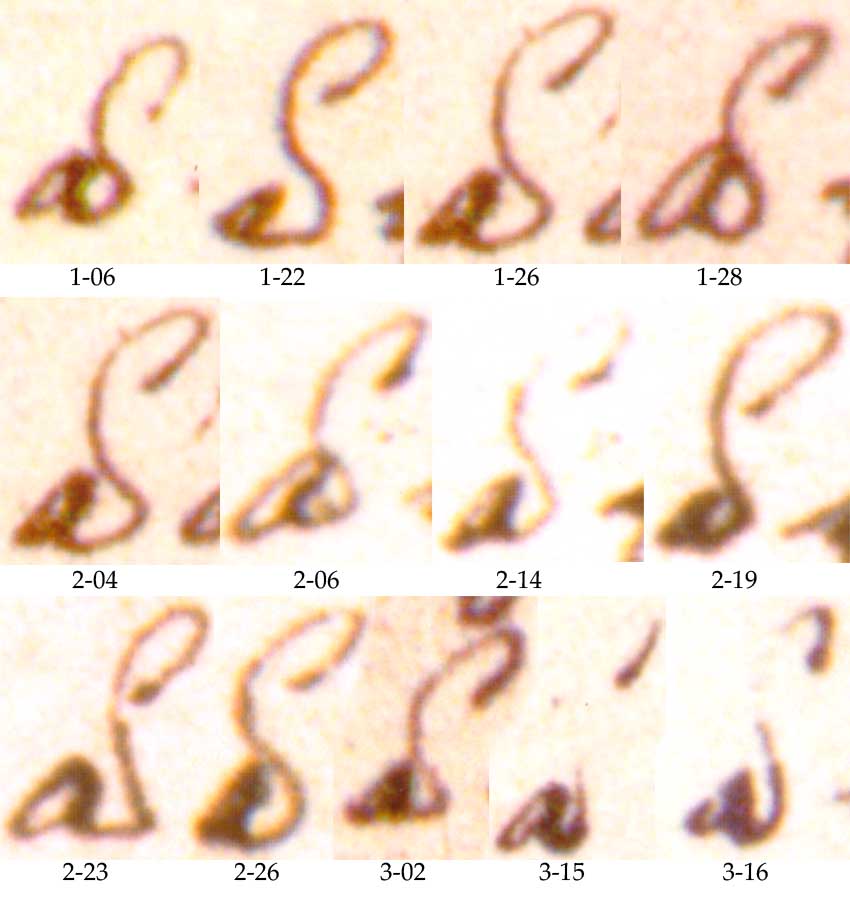

2.6 The sigma-tau ligature (stigma) in στρωματέως

There are 20 additional stigmas that are not at the beginning of words and 12 of these that are combined with the preceding letter will be displayed later in 3.5 Between the alpha and the tau in ἐνσωμάτων. The remaining 8 unattached stigmas are presented below. Number 3-17 is definitely corrected and overwritten. Otherwise they all look fairly similar. For now, we can only say that the stigma in στρωματέως, has an ink blob that could be an overwritten letter (although no traces of it can be seen) or just a drop of ink on top of an otherwise properly written stigma.

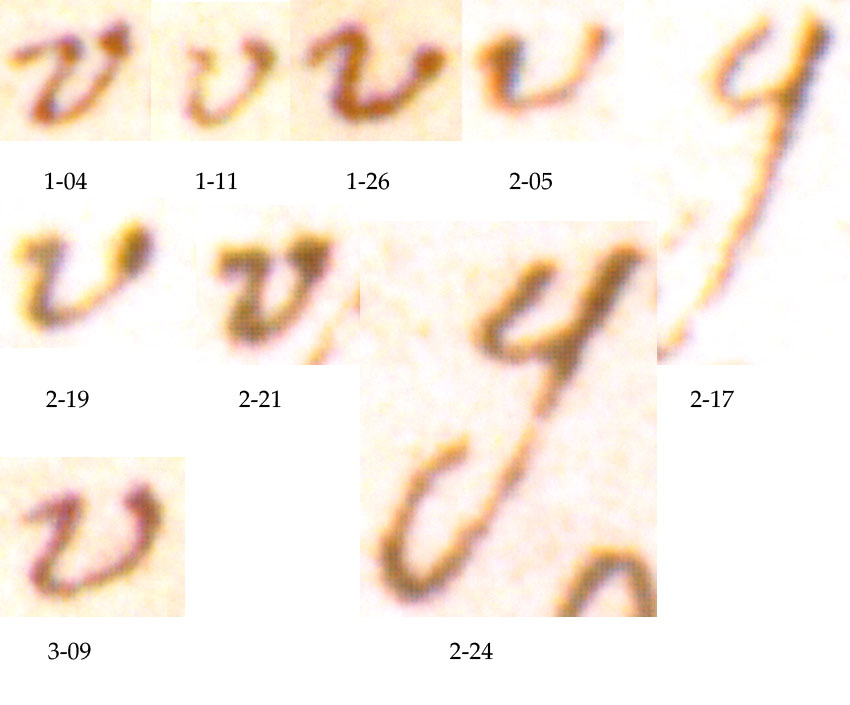

2.7 The upsilon in (ὁ- )δοῦ

Further Carlson sees an ink blob “betraying hesitation … at the beginning of the upsilon in (ὁ- )δοῦ” in line 4 on page 1. Carlson also says that

“it is the only instance in the manuscript in which the scribe failed to use a ligature for the omicron-upsilon pair.”

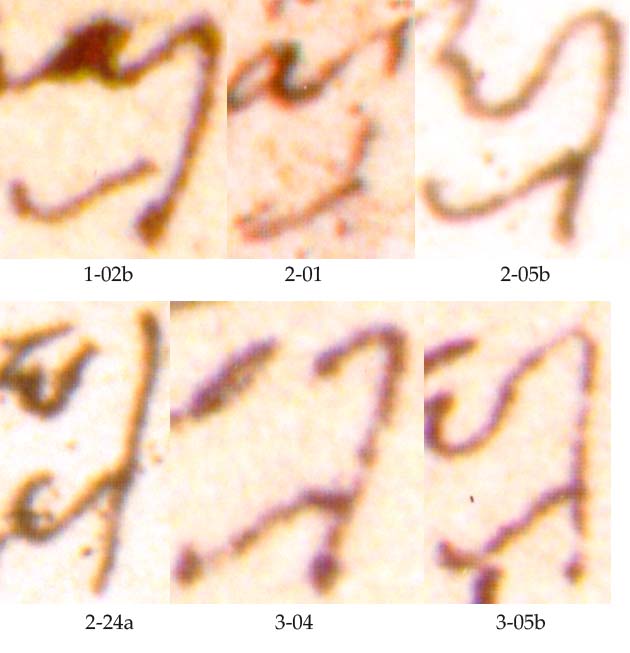

Since it is the only instance, there of course are no other disconnected omicron-upsilon pairs to compare it with. I have though found a few upsilons which are not connected at the beginning and therefore resemble the upsilon Carlson refers to.

Although none of these upsilons continues upward, there are in some instances similar blobs at the beginning, at least in 2-05.

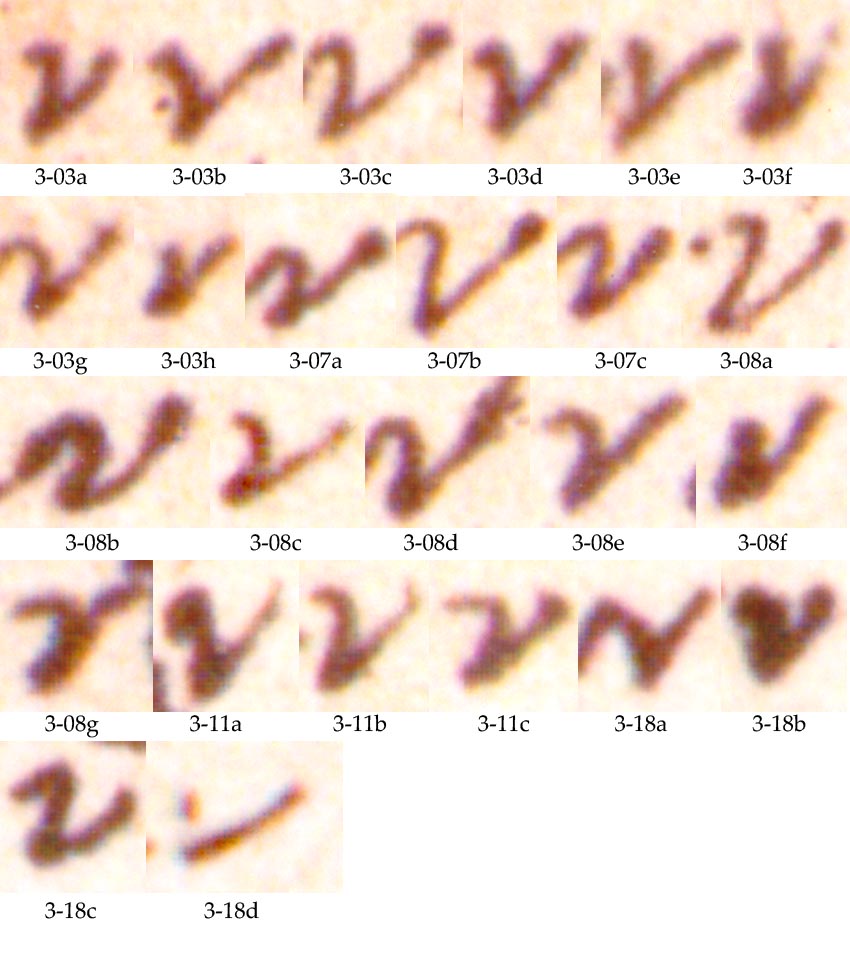

2.8 The nus in ἀπέρατον and σαρκικῶν

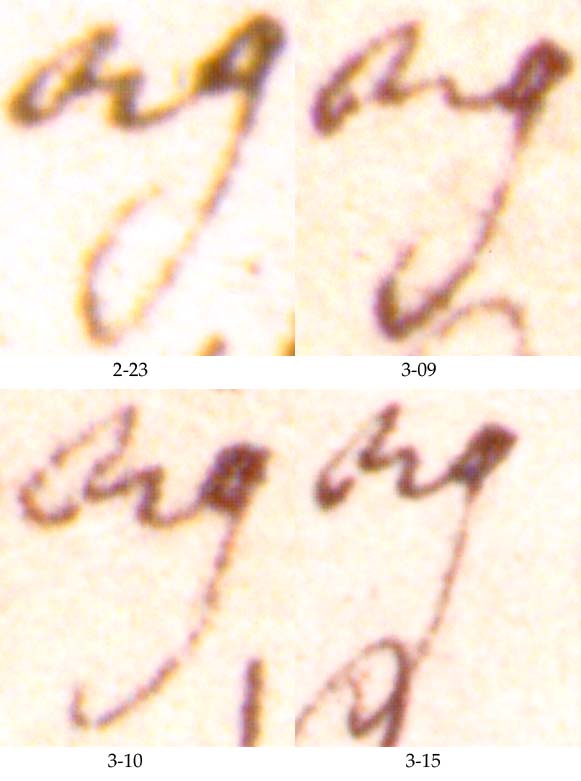

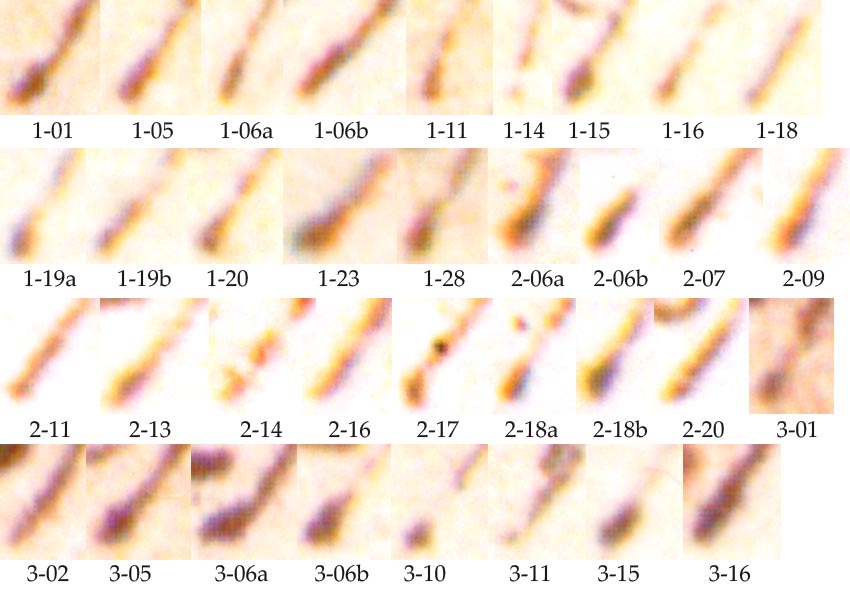

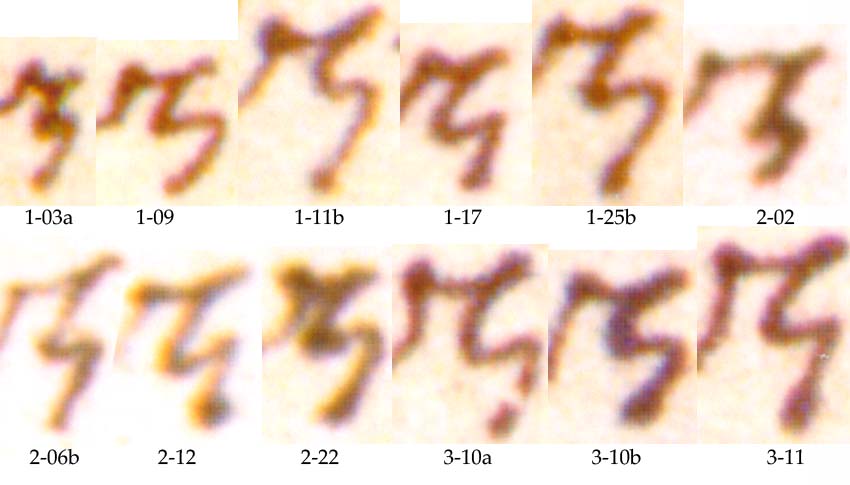

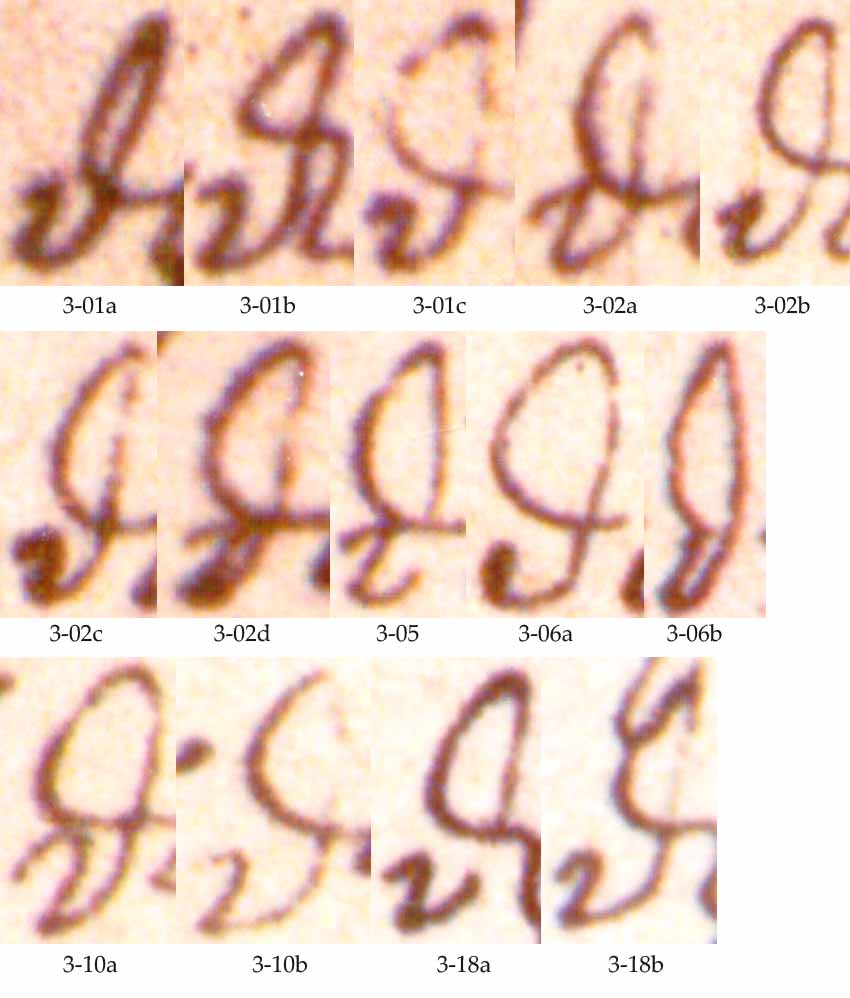

The next word is ἀπέρατον in which Carlson sees (an) ink blob in the nu. He also sees one in the same line in “the nu in σαρκικῶν”. They are both taken from line 4 on page 1 and are presented to the right. The letter nu occurs in this shape almost 300 times throughout the document, and I present just a few comparative samples (for a more high-resolution image, click here!). It is all instances where the nu occurs in the lines 3, 7, 8, 11 and 18 on page 3. I have chosen page 3, since Carlson claims that the writing improved and that the hand was showing more fluidity” on page 2 and especially on page 3. He says that in the “final line of Theodore”, i.e. line 18 on page 3, except “for the first few words, the writing is noticeably more fluid”. But the first few words are also part of line 18 and overall the writing to me seems to be similar throughout the manuscript.

I cannot in any way see that these examples from page 3 show a more fluid hand resulting in less ink blobs in the nus, compared to the two examples from page 1 which Carlson has chosen to illustrate the scribe’s hesitation.

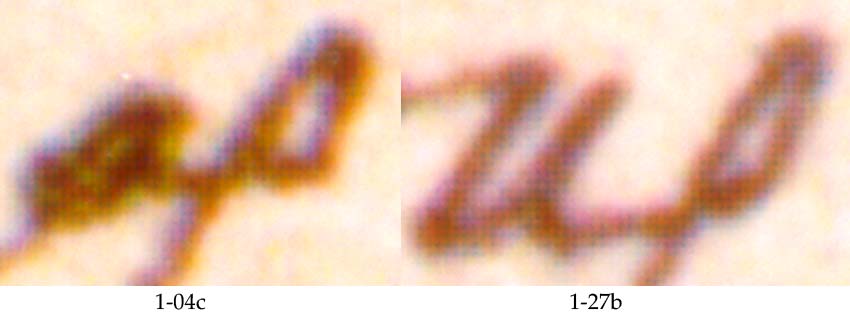

The next word is ἄβυσσον in line 4 on page 1, where Carlson discovers hesitation and ink blobs in “the first sigma of ἄβυσσον”. I provide all the sigmas in Theodore which are of the same type and resemble the sigma Carlson refers to (provided to the right). For more high-resolution images, click here and here!

Although I am not certain of which ink blob Carlson refers to, the one at the top of the letter or the one at the end of the horizontal line to the right, it is easy to see that similar “blobs” occur virtually everywhere in the document. The “blob” at the top of the sigma comes from the scribe’s habit of making a loop. If the loop is wide, it will show as in 2-16a, 2-16b and 3-04. If the loop is narrower, then it turns out like the sigmas in 1-06, 1-14b, 1-27b and so on – just like in Carlson’s example.

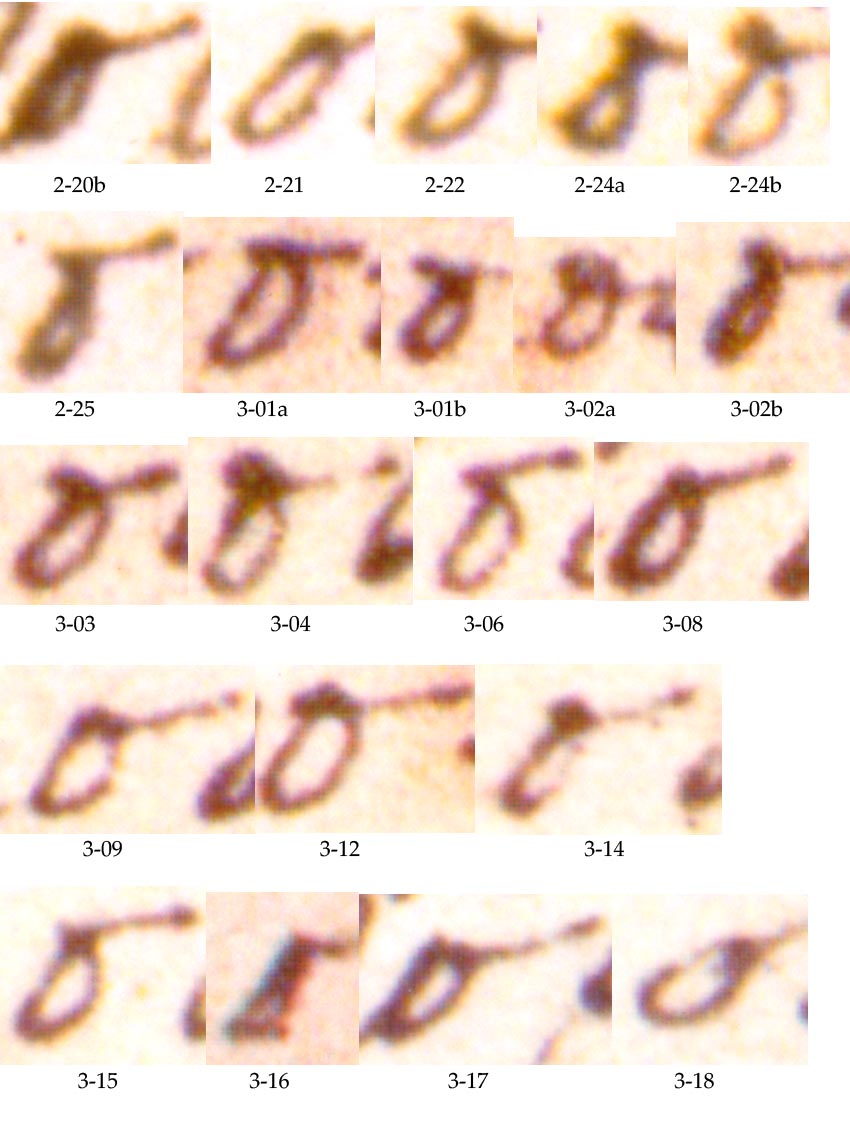

2.10 The taus in the two instances of τοῦ

Next we turn to page 2 of the manuscript, line 18, where Carlson thinks that

“the letters are more quickly written, with more flying ends, yet blunt ends are still found throughout and ink blobs at the taus in the two instances of τοῦ”.

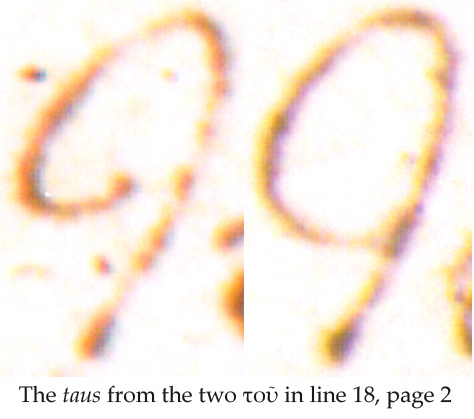

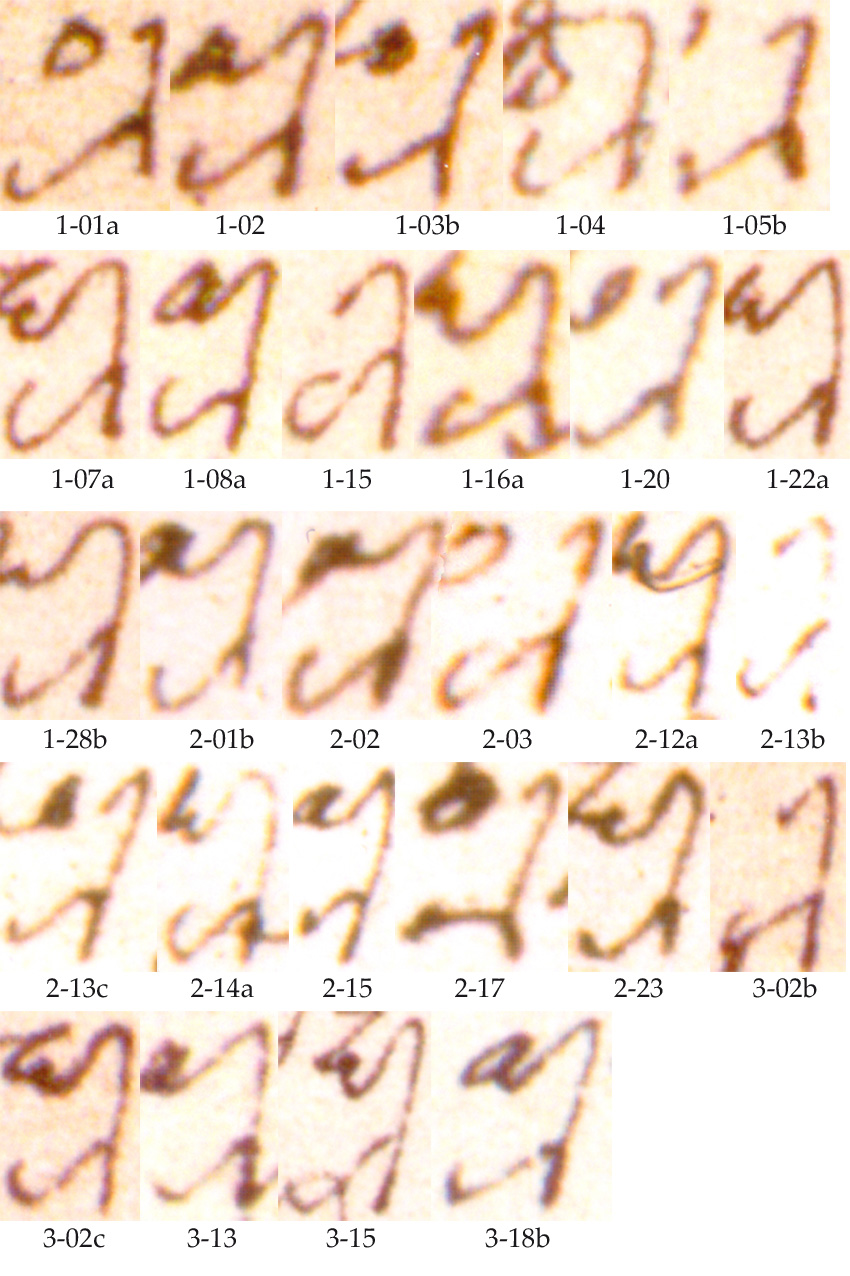

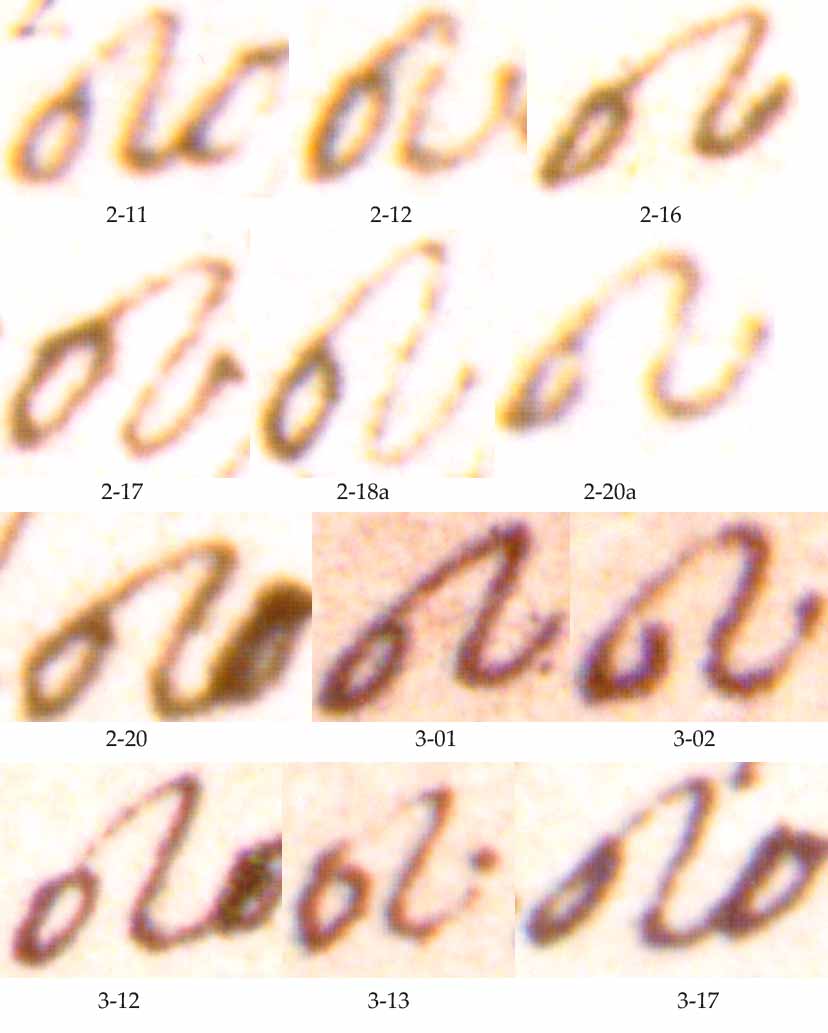

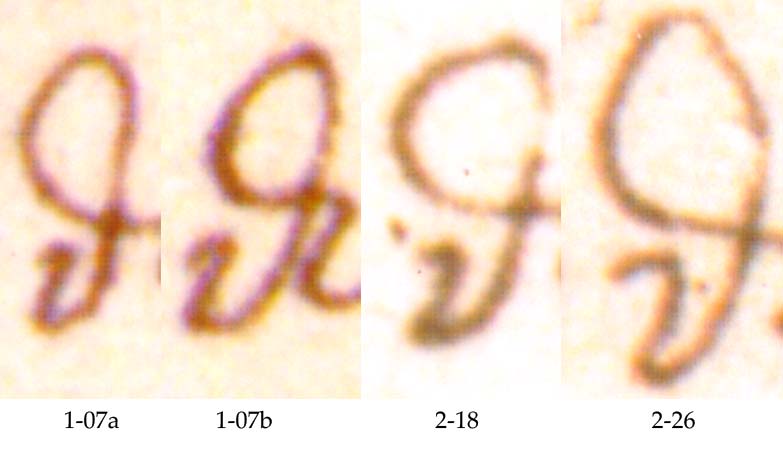

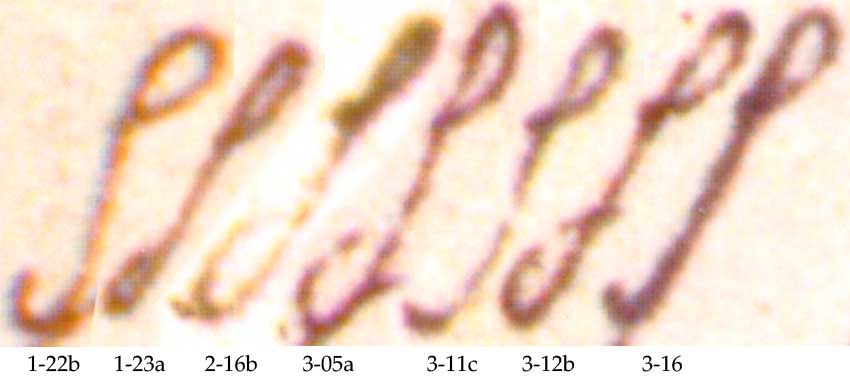

Since there are so many taus, I have settled for picking out all taus from the 35 τοῦ in the manuscript where the tall tau is used in the same way as in this example. I have also included the two taus from Carlson’s example (named 2-18a and 2-18b) and then reproduced only the lower end of the letters; the part where Carlson sees ink blobs.

First of all one can say that Carlson’s example, 2-18a and 2-18b, does not deviate in any particular way from the other taus. There are taus with both larger and smaller blobs at the ends. Secondly, there are really no big differences between the first written and the last written taus. Carlson claims that as work proceeded, the letters were more swiftly written, with more flying ends, and therefore the blunt ends and the ink blobs, although present, became fewer and fewer and less conspicuous. But in these examples, chosen haphazardly by picking out all taus from the word τοῦ, there seems to be no improvement over time. In fact, if there are any differences, there seem to be more blunt ends, and also more marked blunt ends, among the taus in page 3 than in page 1.

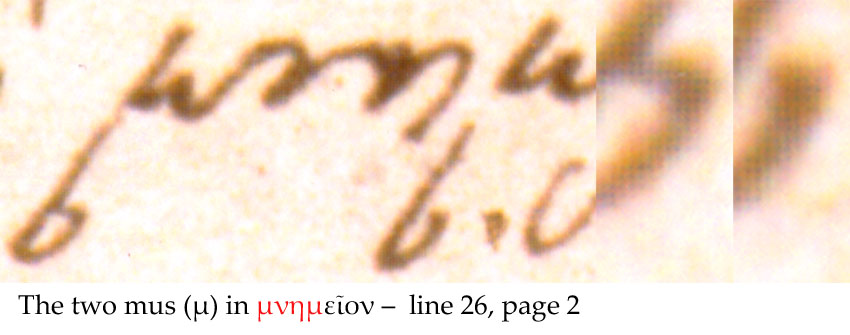

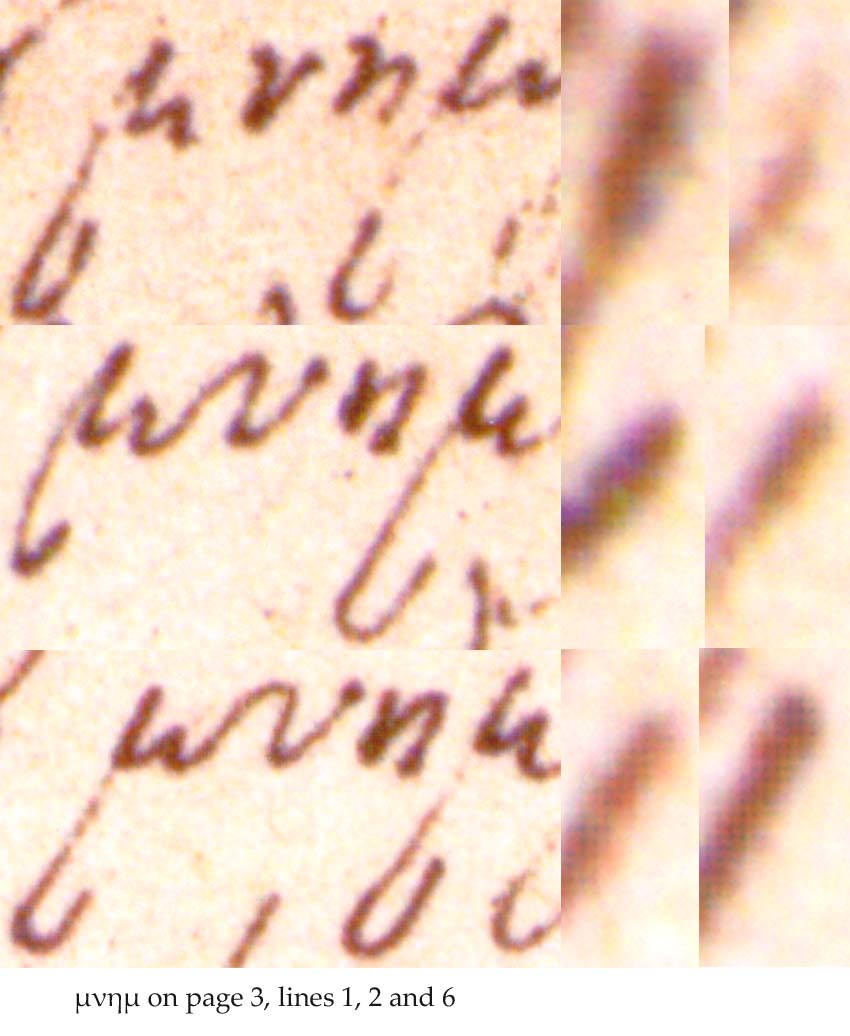

2.11 The mus in μνημεῖον

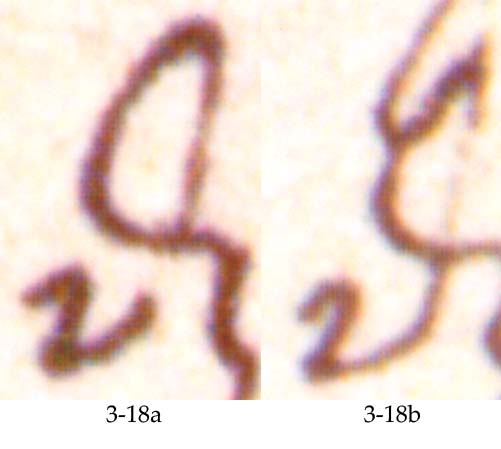

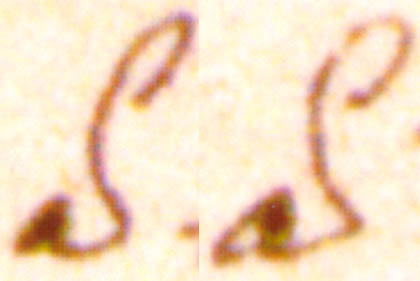

In the last line of the second page (2.26) Carlson thinks that

“the hand is showing more fluidity. The number of ink blobs at the ends of lines is reduced over the previous lines, though a few still remain, e.g., at the beginning of both mus in μνημεῖον”.

To me there seems to be no blobs at all at the beginning of either of the two mus. The first one, with the first enlarged beginning reproduced just right of the image of μνημ, definitely begins with a slight horizontal movement, possibly a hook, before turning downwards. There is no blob. The second mu with its enlarged beginning furthest to the right has no hook but also no blob.

There are all together 117 mus in the manuscript. I reproduce only 6 of them, all coming from page 3 and the only other 3 times in the entire manuscript when a word begins with the letters μνημ, the same as in Carlson’s example.

I can see no real differences between these examples from page 3 (where Carlson claims that there are less ink blobs) and those presented by Carlson from page 2 of the manuscript. The only thing that can be said for certain is that if there are blunt ends with ink blobs in Carlson’s example, then there are blunt ends with ink blobs also in the other six instances on page 3.

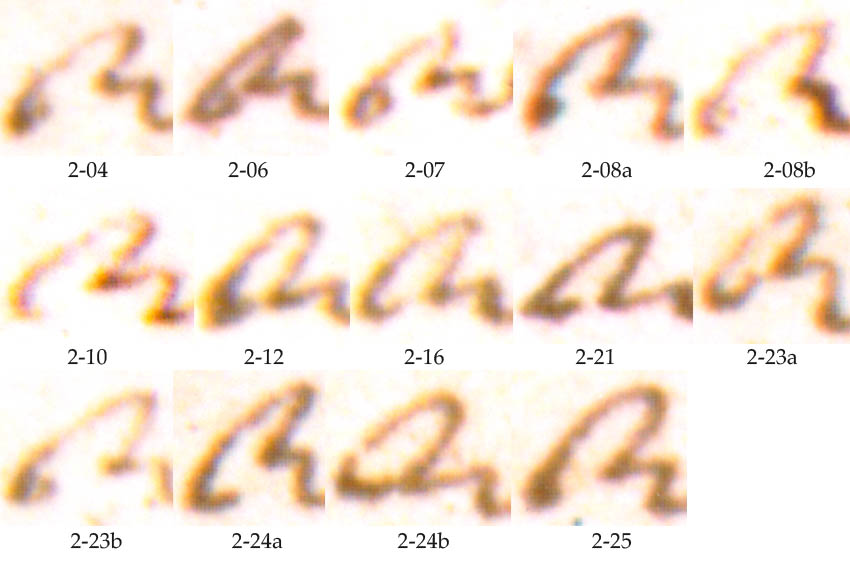

2.12 The beginning of kappa in καὶ

As can clearly be seen, there is always a hook at the beginning of the kappa and if it is narrow, like in 2-08a or 2-25 (or as in Carlson’s example 2-26), it turns out like a blob.

2.13 The left leg of the two-stroke lambda in ἀληθὴς

The last example of ink blobs, Carlson picks from the last line on page 3, i.e. line 18. He says:

“The left leg of the two stroke lambda in ἀληθὴς is written deliberately, as evidenced by the large blobs of ink at both ends”.

Here Carlson by all means is correct in that the ink blobs are particularly conspicuous. The scribe normally used a lambda which he wrote in one stroke. Of a total of 111 lambdas, there are only 7 which with certainty can be said to have been written in two strokes, where the scribe lifted the pen at the bottom of the vertical line and began the left leg anew, either from some point on the right leg or to the left connecting to the right leg. This is one of those 7 instances of a two-stroke lambda. The remaining 6 two-stroke lambdas, excluding this one, are presented below.

Although none of these 6 examples comes out as strongly, still there are blobs, particularly at the left end of the left leg.

There are an additional 27 lambdas which for different reasons cannot be determined whether they are written in one or in two strokes. My guess though is that most of them, if not all of them, were in fact written in one stroke. And for comparison, also these 27 lambdas are presented below. For a more high-resolution image, click here!

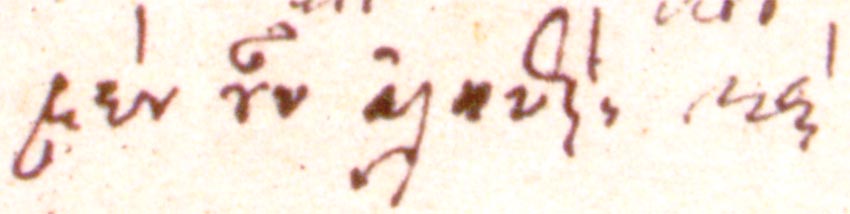

Even though many lambdas have darker areas; accumulations of ink – none really show an ink blob at the beginning of the left leg of the same size as the one in Carlson’s example. There is though something quite strange about the three words in the beginning of the last line (18) of the manuscript; “μὲν οὖν ἀληθὴς” (from where Carlson’s lambda is taken). They are strikingly different compared to the remaining words on the last line and also quite different compared to the other words in page 3, in that they are darker and thicker than the rest. I give the beginning of the last line with also the following καὶ included, which is much fainter and more in line with the rest of the text on line 18 (click here for a larger image).

One could suspect that the scribe has tried to improve the writing in the beginning of the line by simply filling in the letters with more visible ink. I am however unable to spot any underlying text; any letter sticking out where the scribe has slipped and simply not been able to cover the underlying letter. There are a number of difficult passages, even those with a minimum of ink, and still no signs of any underlying writings, so I consider that option to be unlikely. Although I have no rational explanation of how these opening words became much darker than the following words, it must be due to the quill pen leaving more ink than it normally did. This of course would explain why there are so large ink blobs in the lambda, although it really is no explanation. It is nevertheless strange that these first words of the last line, μὲν οὖν ἀληθὴς, means “now the true explanation”, which of course is not given as the copy does not contain the ending of the letter.

Interesting though, if the two-stroke lambdas can be seen as “mistakes” there are only one such mistake in page 1, whereas there are three each in the following two pages. This contradicts Carlson’s assertion that the scribe became more confident the longer he wrote.

2.14 Summary of the ink blob problems

Carlson considers the Mar Saba Letter to be a modern forgery made by Morton Smith; although he has chosen to call it a hoax instead of a forgery. In analyzing the handwriting, he claims that the style gives the impression that the letter was written in a swift hand, whereas in reality it was written very slowly by someone trying to imitate a hurried writing. This can, according to Carlson, be shown by among other things the hesitation in the writing leading to blunt ends instead of flying ends and often ink blobs where the pen had come to a complete stop. There are without any doubt many blobs in the manuscript. As I have compared Carlson’s example only with other letters taken from the same manuscript, it will of course not be possible to judge whether or not these blobs are due to a slow handwriting. In order to do so the writing in the Mar Saba Letter will have to be compared with many other similar eighteenth-century cursive handwritings, specifically with tiny writings, as the Mar Saba Letter is written with very small letters. If none of these other texts show any ink blobs, then that is an indicator that the Mar Saba Letter was in fact written unusually slowly.

Carlson claims that the most obvious mistakes and signs of forgery are at the beginning, and these characteristics become less obvious as the work progresses. But in those instances where I have compared the letters or combinations of letters, in search for ink blobs, there really seem to be no differences between the first and the last pages. The short tau (2.3) and the iota (2.4) show in page 2 similar blobs as in page 1. The omicron-upsilon ligature (2.5) shows clearly visible blobs at the end in 3 of 7 instances (43%) on page 3, while they occur only in 5 of the 16 instances on page 1 (31%). The 26 nus on page 3 (2.8) differ in no way from the 2 examples on page 1 given by Carlson. The 15 sigmas from page 3 (2.9) are generally even more awkwardly written and contain more blobs than those on the previous two pages. The same goes for the ending of the tall tau (2.10), where the blobs are even more conspicuous on page 3 than they are on the two preceding pages. And the lambdas (2.13) show no improvement over time—rather, quite the contrary. This contradicts Carlson’s claim that the scribe was uncertain but became more certain as work proceeded, at least when it comes to the number of ink blobs and their sizes.

Further it can be seen that of the two examples of tau in τῶν (2.3) the first is not an ink blob, but a rewrite, and the second blob is due to the fact that the scribe made hooks at the bottom of every tau and also narrow turnings at the top. The iota (2.4) really has no blob but a small hook. The blob at the end of the omicron-upsilon ligature (2.5) coincides with other omicron-upsilon ligatures, which also end rather abruptly. The sigma-tau ligature (2.6) is correctly written, and there is no way of knowing how the large ink blob in the middle came into being. The beginning of the upsilon in (ὁ- )δοῦ (2.7) is a bit darker and wider compared to what follows, and similar “blobs” are found at the beginning of other upsilons. Only one of the mus in μνημεῖον possibly shows a blunt beginning, but no blobs. The blob which Carlson sees at the beginning of the kappa in καὶ (2.12) probably arose from the scribe’s habit of beginning the kappa with a (narrow) hook, and the blobs at the final lambda (2.13) corresponds to the much darker surrounding writing.

So, all that really can be said about the ink blobs is that they occur in the manuscript. Some can be accounted for by peculiarities in the scribe’s style, others perhaps result from the very tiny writing, and still others are manifest throughout the document. In no objective way can it be shown that there are more and larger blobs at the beginning than at the end.

3.1 The line connecting the epsilon and the kappa in ἐκ

Carlson further claims that the scribe stopped, lifted the pen and began anew, although a skilled scribe would have written it in one stroke. He writes:

“The next word is ἐκ … and it shows another tell-tale sign of forgery—the pen

lift. More specifically, the line connecting the epsilon and the kappa

shows evidence that it was written in two different strokes. First, the pen was

lifted after the epsilon and the writer tried to continue the next stroke

along the same course but the ink flowed back to the end of the first stroke,

leaving a blob of ink in the middle of a stroke. This pen lift

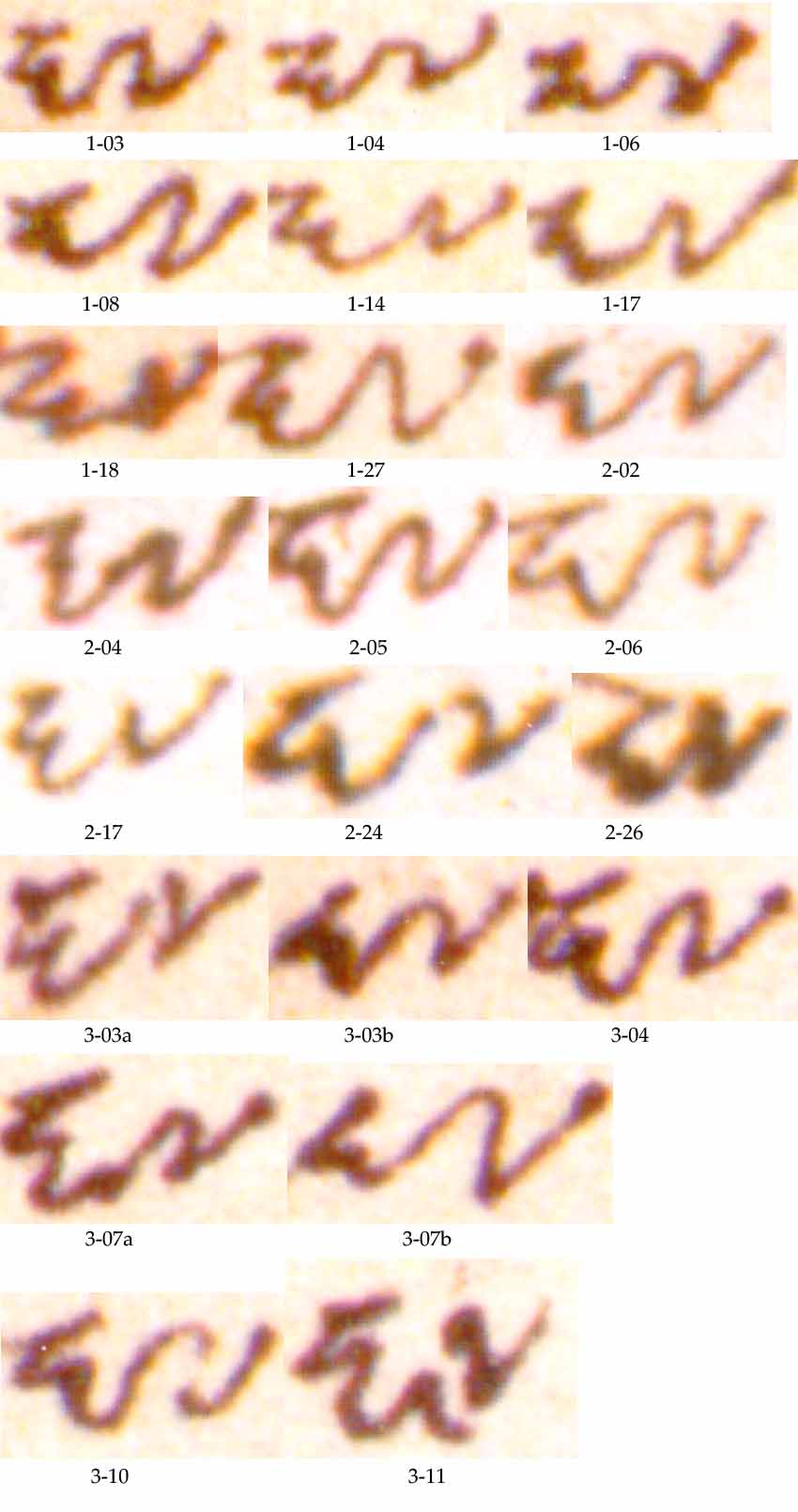

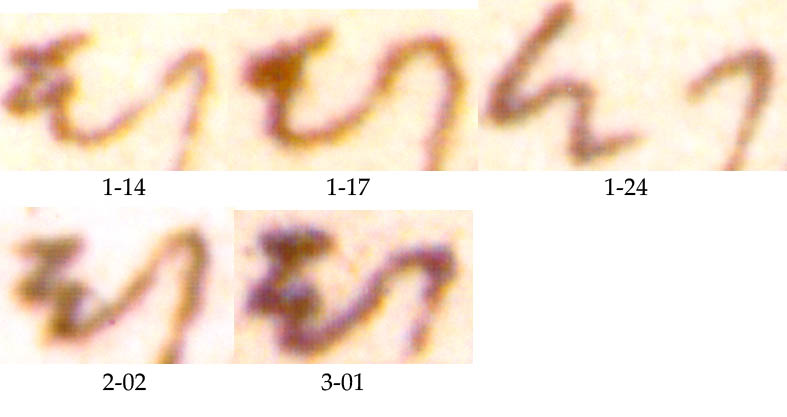

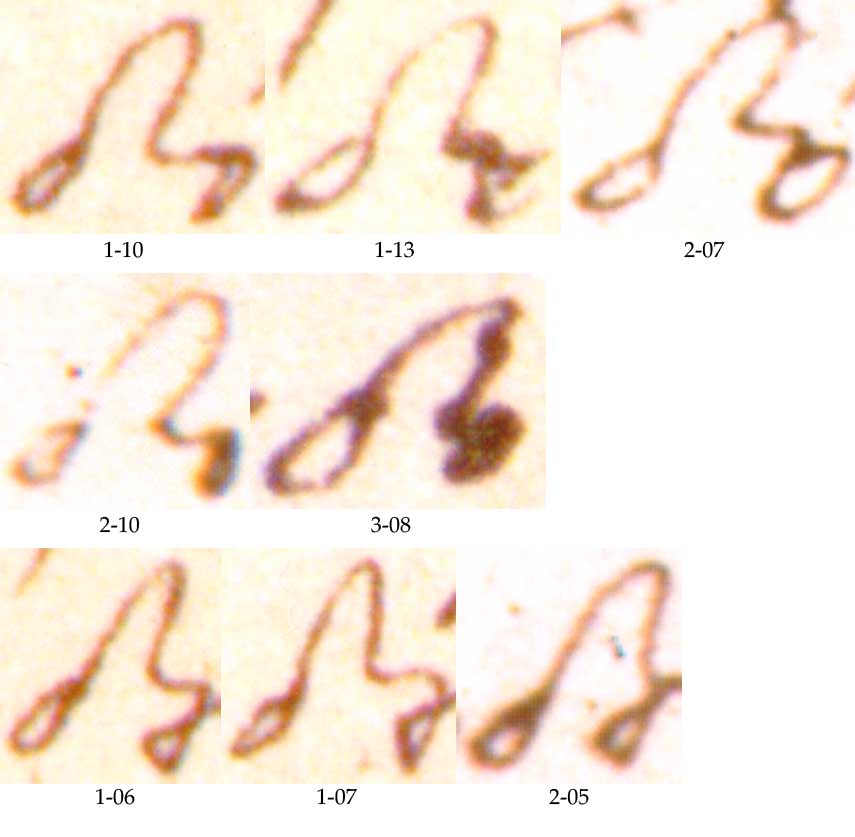

The word ἐκ is in line 1 on page 1 and is reproduced to the right. Here Carlson is obviously wrong, when he claims that “the writer tried to continue the next stroke along the same course”. The truth is that he just happened to connect the two letters, which are written separately. As previously said, the scribe never connects the letter kappa to the preceding letter, never once in the entire manuscript. He writes it separately and begins it with a hook at the base. Sometime the hook is wide; sometime it is tighter and then the hook can turn into a blob of ink. I settle for showing the 17 instances when ἐκ occur, leaving out all other kappas; those that are not preceded by epsilon. For more high-resolution images, click here and here!

As can clearly be seen, kappa is always written separately, starting with a hook on the lower left leg. In 2-05 there is a tight hook resulting in an ink blob and in 3-05 the letters are written so closely that epsilon and kappa touch each other, giving a false impression that they were bound together, as in Carlson’s example. In 3-05 it is possible that the scribe wrote the epsilon in a similar way as the one presented to the right which comes from the line 11 on page 3.

3.2 The stroke between the omicron-upsilon ligature and the circumflex accent in τοῦ

“Other pen lifts on Theodore 1.1 in unusual places are found on the stroke between the omicron-upsilon ligature and the circumflex accent in the first τοῦ”.

Now, in the connection there is obviously a curve and also a slightly darker area. However, darker and lighter areas succeed one another continuously in the manuscript and the curve or bend in the connection is rather a peculiarity in which the scribe wrote these connections, than a “retake” – as will be shown. Below I present a selection from the manuscript of the omicron-upsilon ligatures with a circumflex accent. All of the examples in the entire manuscript can be found in three tables: Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

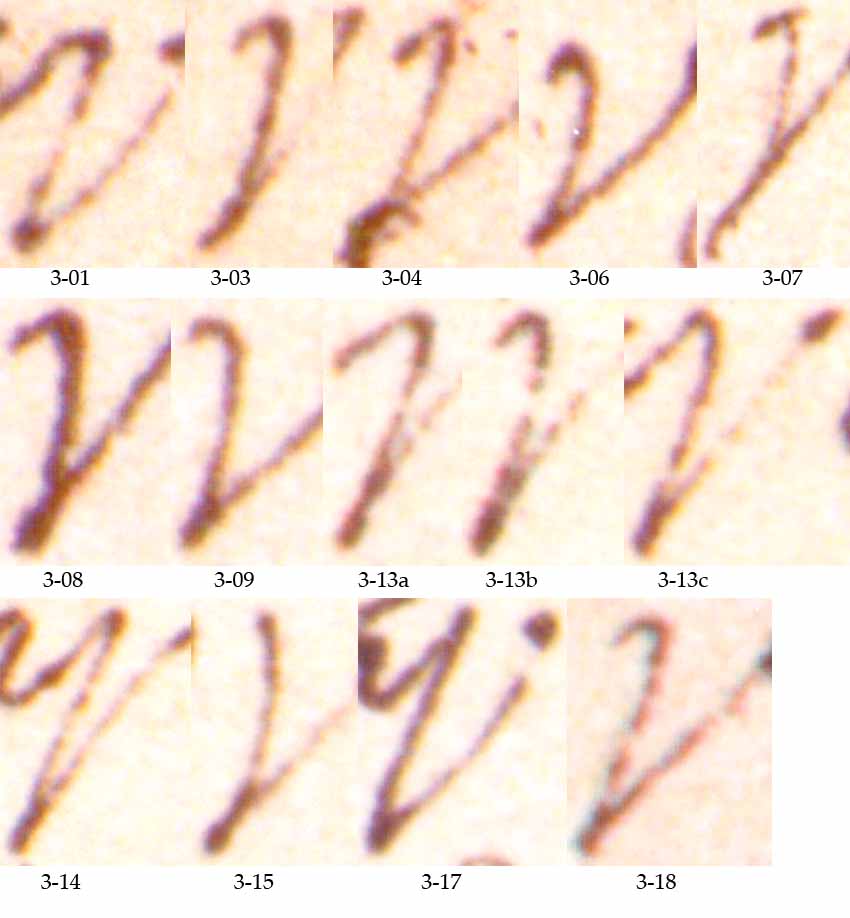

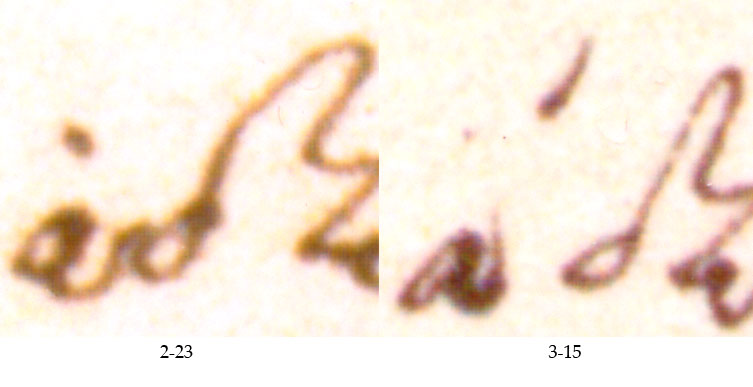

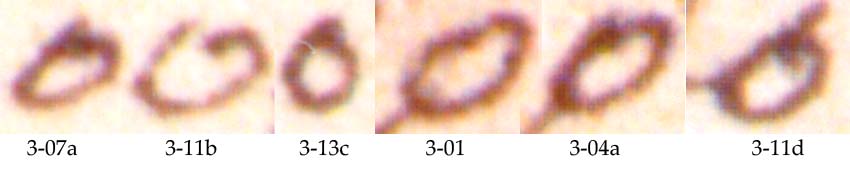

3.3 The stroke connecting the epsilon and the nu in the word κλήμεντος

As can be seen, there are irregularities and “ink blobs” just about everywhere. Carlson’s thesis is that the stops and pen lifts were mistakes which improved over time. These examples show that irregularities occur regularly throughout all three pages and that the letters are written apart in a few instances, which the scribe does not try to “hide”. In 3-07a and 3-11 the nu is not connected to the epsilon and so could be the case also in 1-18, 2-04, 2-24 and 3-03a. “Blobs” occur in 1-03, 1-04, 1-06, 1-08, 1-14; in 2-04 (which could be a pen lift), in both 2-24 and 3-03 before the stops (probably pen lifts), in 3-03b, 3-04, 3-07 and 3-10.

3.4 The middle of the rho of ἀπέρατον

Carlson claims further that “[p]en lifts are evident in the middle of the rho of ἀπέρατον” in line 4 on page 1. The epsilon-rho combination (έρ) is reproduced to the right. I suppose Carlson sees the pen lift on top of the rho or at the crossing from epsilon to rho. I am however incapable of spotting any pen lift in either of these places. As usual I reproduce other rhos and have selected those that are preceded by an epsilon, and cropped the rho so that only the relevant part is preserved. A more high-resolution image is to be found here!

Also this time the rhos seem fairly similar compared to the example given by Carlson.

3.5 Between the alpha and the tau in

ἐνσωμάτων

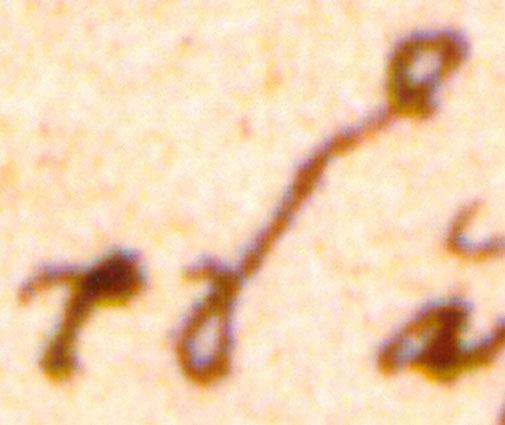

Carlson gives another example of pen lift from line 4, “between the alpha and the tau in ἐνσωμάτων”. In the word ἐνσωμάτων the small tau needs to be used, since the ending -ων is marked above the tau. As far as I can see, apart from this one instance, there are only two other examples of small taus following other letters, and that is in the word μετ’. In both of these instances there are similar blobs in the passing from epsilon to tau as is shown below.

The small tau is otherwise always written separately and then only in the word τῶν. The closest one can get is the stigma (sigma and tau combined), and it is also either written separately, even inside words, or connected in a similar way as with the tau, and often also showing blobs. Below are the twelve stigmas in the document that are connected with the preceding letter. The 11 unconnected stigmas were presented earlier in 2.6 The sigma-tau ligature (stigma) in στρωματέως.

So to me it seems likely that the scribe either normally wrote the small tau by itself and did not combine it with other letters and therefore lifted the pen when he began with the tau, or just made a stop before changing direction, as seems to be the case every time when the stigma was connected with the preceding letter.

3.6 The left leg of the lambda in δοῦλοι

Next we turn to “the left leg of the lambda in δοῦλοι” in line 7 on page 1, where Carlson sees “[u]nnatural pen lifts in the middle of what should be” a smooth curve. The left leg of the lambda (λ) is somewhat uneven, but I see no sign of a pen lift, especially as the stroke was written with a quill pen. Perhaps Carlson noticed the bottom right, where there is a short distance with very faint colour, but that is hardly the result of a pen lift in any other way than that the scribe wrote with a little less pressure than what he normally did. Besides, we do not know how much was left out by the photograph and how much that might have faded away during the years. There are of course an enormous amount of lambdas in the manuscript, to be precise 111, and it would hardly be meaningful to reproduce them all, especially since I do not know where the pen should have been lifted, and therefore do not know what to notice and refute. In 4.2 The lambda of δοῦλοι I have though presented a selection of, what I consider to be, 25 one stroke lambdas.

3.7 Between the epsilon and gamma of γεγόνασιν

There is however other signs and those can be seen in the five instances in the manuscript where gamma follows epsilon (εγ).

As can be seen, in 1-24 the letters are written apart, although no signs of blobs appear. In all the other four instances there is also a similar thinner and more faded part just where the fainter passage also occurs on the example provided by Carlson. This to me seems to indicate that the scribe normally was easing the pressure on the quill pen as he was moving from epsilon to gamma.

3.8 Between the pi and the epsilon of

ἐπιθυμιῶν

Another pen lift in line 7 is, according to Carlson, found “between the pi and the epsilon of ἐπιθυμιῶν”. I have reproduced ἐπι to the right and if one looks carefully, one can on the line connecting ἐ and π actually see five places where the line bulge and there is also one darker dot at the turn at the top. I must say that I am unable to spot any pen lift. The one blob which could be the pen lift Carlson was referring to is actually on the pi or between the pi and the iota. That is if Carlson made a mistake and wrote epsilon instead of iota. That ink blob probably though comes from the scribe making the pi too narrow.

It is nevertheless interesting to examine the additional fifteen instances in the manuscript where the combination epsilon–pi occurs. On three occasions the accent is connected directly from the epsilon in ἐπι, and the epsilon and pi therefore of course are not connected.

The remaining 12 epsilon–pi combinations are presented below and an image of higher resolution is found here.

Apart from 3-08, the other eleven epsilon–pi combinations actually are written apart; i.e., like the kappa, the pi is normally not connected to the preceding epsilon. There are though two exceptions; number 3-08 and Carlson’s example from line 7 of page 1. If Carlson was referring to the top of the stroke connecting to the pi, as the place where the pen lift should have occurred, I would say that in 3-08 there is a much more obvious example of a pen lift, leading to a large ink blob. The reason for this seems to be that the scribe normally lifted the pen after writing epsilon before beginning to construct the pi separately. So, if this was the case in Carlson’s example, it would seem as quite normal for this particular scribe to do so.

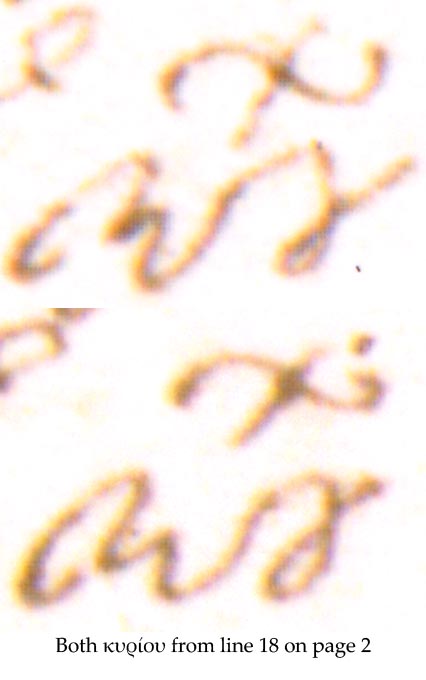

3.9 Between the kappa and the omicron-upsilon ligature in κυρίου

In line 18 on page 2, Carlson sees pen lifts in both κυρίου (Lord). He says:

“Both abbreviated instances of κυρίου show pen lifts between the initial kappa and the final omicron-upsilon ligature”

If one looks closely there is a darker area in the first κυρίου where the stroke between the kappa and the omicron-upsilon ligature makes a curve to the right. If the scribe tried to connect to the line where he had made a break, then the darker area would be where he put down the pen and began the new stroke. However the darker area begins below the curve without any noticeable change, just slowly getting darker, and then all by a sudden becomes lighter. In fact it ought to be the other way around if Carlson is correct. If the text would have been written in the opposite direction, then the darker area begins almost instantly and thereafter slowly gets less dark. This is even more obvious in the second example, where we are to believe that the scribe ended with a darker area resulting in a blob and thereafter connected to the line with a barely visible stroke which got darker and darker as he moved the pen.

The abbreviated word κυρίου occur 7 more times in the document, and I present all of these below:

If we are to believe that the scribe wrote κυρίου slowly on two occasions in line 18 on page 2 and lifted the pen “between the initial kappa and the final omicron-upsilon ligature”, then we must suspect that he did so also the other seven times, since in all of these other example similar “traces” can be found. Perhaps he just wrote the kappa, then the abbreviation above, and finally connected the ου-ligature to the kappa? In which case, all nine instances of the word κυρίου are written in a consistent way.

3.10 Between the epsilon and the upsilon in ἐλευθερία

Carlson also sees another pen lift in line 18 on page 2 “between the epsilon and the upsilon in ἐλευθερία”. Also this time I am unable to spot where the pen lift should have occurred. According to Carlson’s information it ought to be on the stroke up from ε to the top, and there is clearly a lighter area in that stroke, however not because of a pen lift. Then there are darker areas on the stroke from the top down to υ, but none of these seems to be the result of a pen lift. Below are the other 24 instances where the ευ-combination occurs and they can also be viewed in higher resolution in table 1 and table 2.

In the additional 24 combinations of epsilon-upsilon, darker wider areas succeed lighter narrower areas which in turn succeed darker areas, and so on. I cannot see in what way Carlson’s example deviate from these examples.

3.11 Between the epsilon and tau in μετ’

“In the next word, μετ’, there are two pen lifts on the connecting line between the epsilon and tau, which may have been added later in retouching”.

This word μετ’ was previously analyzed in 3.5 Between the alpha and the tau in ἐνσωμάτων (image 2-26), in dealing with the connection to tau. Carlson speaks of two pen lifts. One I suppose is the “blob” on top connecting to the tau. This was shown to be the result of the scribe either writing the small tau by itself or just making a stop before changing direction. The scribe normally wrote the small tau by itself and when he combined it with the preceding letter he always made a stop and changed direction, which resulted in a blob. This is also seen every time when the stigma is connected to the preceding letter.

The other pen lift which Carlson sees ought to be at the bottom just turning upwards from the epsilon. That could very well be a pen lift and that the scribe started anew although it is hard to say. If there is a later retouching is also impossible to tell, but the only reason for suspecting that would be that the lines are thick. The lines are, however, often thick and that seems to be the result from the text being tiny and irregularities get enhanced when the images are enlarged as much as they are here. The other instances of retouching which Carlson refers to, shall however be examined.

3.12 Summary of the pen lifts

Carlson finds pen lifts in places where he thinks that they normally should not have occurred if the text would have been written by a skilled scribe in the eighteenth century. His first example is from between the epsilon and the kappa in ἐκ (3.1). This clearly is wrong, due to the fact that the scribe always wrote the kappa separately and never connected it to the preceding letter. The next example with the stroke between the omicron-upsilon ligature and the circumflex accent in τοῦ (3.2) shows no clear pen lift, but rather a peculiarity in which the scribe wrote these connections, shown in many other places. Also the stroke connecting the epsilon and the nu in κλήμεντος (3.3) really cannot be concluded to be a pen lift. In fact the slightly darker areas correspond with many other combinations of εν. The same goes for the pen lift in the middle of the rho of ἀπέρατον (3.4) where no obvious pen lift can be seen and where the letter rho in other places looks fairly similar. The pen lift between the alpha and the tau (3.5) is either due to the scribe’s habit of writing the tau separately or, more likely, his habit of changing direction when connecting to the short tau, or for that sake, also the stigma. The same thing holds true for one of the pen lifts Carlson sees in the connection from the epsilon to the tau in μετ’ (3.11). The other suspected pen lift, could be a pen lift, but that is hard to decide. I can se no signs of a pen lift in the left leg of the lambda (3.6) or between the epsilon and gamma (3.7). Instead this connection between epsilon and gamma normally shows less pressure on the pen giving the (false) impression of the pen being lifted. It is uncertain where Carlson saw the pen lift between the pi and the epsilon of ἐπιθυμιῶν (3.8), and I am unable to spot it. The connection between the kappa and the omicron-upsilon ligature in κυρίου do show signs which could be traces of the pen being lifted. But then these signs occur also the other seven times when the word κυρίου appear, so this might be another peculiarity in this particular scribe’s way of writing. I am also unable to spot the supposed pen lift between the epsilon and the upsilon (3.10); and the other 24 instances where this particular combination is found, differ in no way from Carlson’s example.

Out of the 11 examples of pen lifts presented by Carlson, none can with certainty be proven to be a pen lift. I am in fact unable to even spot a few, and some are clearly not irregularities due to the pen being lifted. I therefore find no reason for letting the supposed pen lifts provide proof of the letter being a forgery.

4. Retouching of the letters

4.1 The stigma in Στρωματέως

One of the letters which Carlson thinks has been retouched is the stigma in Στρωματέως; a letter dealt with previously for an ink blob. This is obviously a sort of mistake, but as said before in 2.6 The sigma-tau ligature (stigma) in στρωματέως, we cannot tell if this is a retouch or just an accumulation of ink which somehow ended up here.

4.2 The lambda of δοῦλοι

“Despite the apparent speed of writing that the cursive might indicate, the scribe had enough time to go back and retouch some of the letters. For example, the lambda of δοῦλοι, however, shows a lot of retouching and the letter still looks poor”

This is the same lambda as was analyzed in 3.6 The left leg of the lambda in δοῦλοι and in which Carlson saw a pen lift. It is not obvious where the retouching should have taken place, but I suppose Carlson refers to the darker areas which can be seen both at the top of the lambda and at its left leg. Of a total of 111 lambdas, I have for comparison picked out 25 of the 77 lambdas, which I with fairly certainty consider to be one stroke lambdas. In almost every of these examples there are blobs, irregularities, tremors, perhaps signs of pen lifts and retouching – i.e. if we are to use the same standard as Carlson uses when determining these features. The table can be found in higher resolution here.

4.3 The tau in τὸ

The final example of retouching which Carlson presents is in line 18 on page 2, where, according to Carlson, the “scribe also has taken the time to retouch the end of the tau in the word τὸ”. It is hard to determine where Carlson sees this retouching. The end of the tau could mean the lower bend to the right leading up to the omicron. But then both the omicron and the beginning of the tau are darker and have thicker wider lines. There are many, many taus in the manuscript, actually more than 300, and it would not be quite meaningful to reproduce them, particularly since the tau Carlson refers to show no clear signs of being retouched.

4.4 Summary of the retouching

There are for certain a few examples where letters have been overwritten and obvious writing errors have been corrected. This are probably the case in 2.3 The tau in τῶν and could be the case in 2.6 The sigma-tau ligature (stigma) in στρωματέως and perhaps also in 2.13 The left leg of the two-stroke lambda in ἀληθὴς. There are also a few other examples, like the stigma (στ) in ἔστιν in line 17 on page 3 (presented to the right), or the word ἀποθνῄσκων in line 28 on page 1 (presented below).

But these are errors which the scribe corrected, and in no way did he try to hide his action. What Carlson is suggesting is instead corrections made by the scribe to hide errors which could reveal that it was a forgery. Corrections made with accuracy to hide obvious pen lifts and with these corrections disguise the spaces between letters. I cannot find any of the three examples put forward by Carlson to be unmistakable examples of any retouching.

5. Inconsistency in the writing

5.1 The short and the tall tau

I will only investigate Stephen Carlson’s claim for inconsistency within The Mar Saba Letter and does not deal with his examples of inconsistency between this letter and other known Mar Saba manuscripts. Carlson only gives a total of three examples of internal inconsistencies. As previously partly quoted in 2.3 The tau in τῶν, Carlson writes:

“The hand also shows a remarkable internal inconsistency in the very first line of Theodore, where the tau of the first τοῦ is short while the tau of the second τοῦ is tall. Overall, in Theodore the scribe shows a marked preference for a tall tau … except in the word τῶν where the short tau is necessary because of an interfering terminal abbreviation for the -ῶν. The one exception is in the very first opportunity to write a tall tau, which should have occurred in the first τοῦ.”

Stephen Carlson is correct in noting that in the first instance of the word τῶν, the short tau is used, while every other time τῶν is written the tall tau is used.

5.2 The omicron-upsilon ligature

“The word (ὁ-) δοῦ on Theodore 1.4 is also noteworthy in that it is the only instance in the manuscript in which the scribe failed to use a ligature for the omicron-upsilon pair.”

This was previously dealt with in 2.7 The upsilon in (ὁ- )δοῦ and is as Carlson claims the only exception.

5.3 The one- and two-stroke lambdas

Further, on page 32 Carlson says:

The lambda in Theodore, on the other hand, is formed in two different ways. One way is a single-stroke “hook” lambda, with the left leg being connected to the bottom of the right leg. There is also a two-stroke lambda in Theodore”

As earlier said in 2.13 The left leg of the two-stroke lambda in ἀληθὴς, there are only 7 of a total of 111 lambdas which with certainty can be said to be two-stroke lambdas. And the question is whether or not it can be seen as natural to vary ones writing of particular letters? If we are to suppose that the letter is a forgery, it is strange that the forger did not manage to write a letter like lambda the same way every time, particularly since we are to believe that the forgery was made very slowly and with consideration? These kinds of varying ways of writing particular letters ought to be natural variations in handwriting. The fact that the lambda is written in two different ways rather strengthen the genuineness the letter, as a forger should have been careful to be consistent, and writing a letter like lambda in a certain way ought to have been a rather easy task to accomplish.

5.4 Evaluation of the inconsistencies

When I examined my own way of writing, I found out that also I did vary my way of forming letters. For instance do I write the letter “r” in two different ways, I often, but not always, put at horizontal stroke through the vertical leg when writing the figure “7”. I sometimes write the letter “a” with a hook at the top, but seldom manage to use it every time as I fall back into my normal way of writing the letter “a”, and so on. I suspect that other people also vary their way of forming letters and find Carlson’s examples to be rather meagre. Two “mistakes”, one where the scribe was using a tau which he normally wrote, but not when writing the word τῶν, one where he “forgot” to connect the omicron-upsilon pair, and rather wrote them separately, but still correct. And finally the use of a letter (lambda) in two different ways.

Otherwise, the Mar Saba Letter is, as far as I can see, written in a very consistent way. I did notice this when I was looking for other examples of similar deviations, and found these other examples of similar ways of forming letters particularly when I searched the same combinations of letters. This can also be studied in the examples presented in this article. This includes writing the kappa separately beginning with a hook (2.12 and 3.1). The irregular connection between the epsilon and the nu (3.3) is particularly irregular just in the connections between epsilon and nu. Every time a stigma is connected with the preceding letter (3.5), it is connected in the same way, leaving a “blob”. All abbreviated instances of κυρίου (3.9), although showing darker areas, still are performed in the same way, and so on.

The smooth breathing of the alpha is either made as a separate stroke

above or connected from the alpha. Whenever alpha is followed by

ρ, σ, ν, λ, κ, χ (and μ) it is also connected to these letters (more than 40

times) and the smooth breathing is marked above the alpha. If, however,

the alpha is followed by a pi or a delta and as these

normally

So all together the scribe is very consistent in his writing, even when we compare certain peculiarities within combinations of letters.

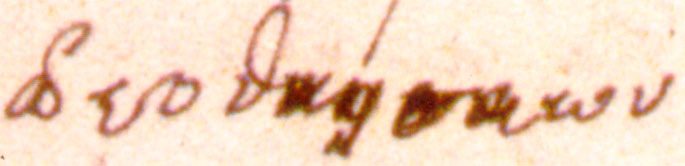

6.1 The theta of Θεοδώρῳ

I have left the forger’s tremor until the end. The reason for that is that the so called tremors are so difficult to evaluate if you only have examples from the same text to compare them with. There are for sure irregularities in the writing; what can be considered tremors, and I will present Carlson’s examples and some comparative material combined with my own analysis. To begin with, Carlson writes:

“The ‘forger’s tremor’ appears in the shaky quality of lines that should be smooth curves. In the first line of Theodore, the shakiness is evident in the theta of Θεοδώρῳ”.

I must say that I find it difficult to spot any shakiness in the theta presented to the right. Carlson refers to tremors in more thetas. In line 7 he finds that “the tremor is still present in the theta … of ἐλευθέρους … and in the theta of ἐπιθυμιῶν”. In page 2 he finds them in line 18 in “the theta of ἐλευθερία” and in line 26 where the “scribe still manifest a tremor in the letter theta, here in the word ἀπῆλθεν”. These four thetas are presented below:

Here the curves obviously are a bit uneven and I suppose this is what Carlson means by “tremors”. Finally he finds a tremor in the last line on page 3 in the word ἀληθῆ. He writes that in the final line

“the writing is noticeably more fluid (e.g., φιλοσοφίαν ἐξήγησις). Even the first theta of ἀληθῆ [sic!] shows less shakiness than before, although the tremor returns in the theta of ἀληθῆ”

(Carlson refers twice to ἀληθῆ. I suppose he meant ἀληθὴς in the first place and in the second place should have written “the second theta of ἀληθῆ”: “μὲν οὖν ἀληθὴς καὶ κατὰ τὴν ἀληθῆ φιλοσοφίαν ἐξήγησις ...”). The two thetas are presented below, with the theta which according to Carlson “shows less shakiness than before” to the left, and the theta which according to Carlson has tremors, to the right.

To me there seems to be no big differences between the two thetas and if any of them show more tremors, it is the first one. The only real tremor that can be detected in the second theta seems to be at the top, but that is due to the intersecting letter above giving that false impression.

There are a total of 60 thetas in the manuscript and I settle for showing the 14 from page 3 (including the two from above) where Carlson considers the text to be less shaky. For an image in higher resolution, click here!

I know of no way to objectively determine whether the tremors are greater at the beginning or at the end. In order to do so, one would need to decide how much deviation from a standard line would count as a tremor, if one should compare how many letters that contain tremors or how many tremors there are in a letter; whether it is the length of the tremor or the numbers of tremors within one letter that counts and how to determine when a tremor ends and a new tremor begins. It seems that all these evaluations are subjective and in the eyes of the observer. As far as I can see though, there seems to be some curves in the thetas in page 3 which are not so even and they corresponds roughly to the two thetas Carlson gave from line 7 on page 1 and the two he gave from page 2. The theta from line 1 on page 1 seems rather smooth compared to the majority of the letters from page 3. The only curve in that example which is not smooth, ought to be the turning at the bottom which is v-shaped, and in such case, then most curves in the examples from page 3 is much less smooth. It seems like the scribe normally made a v-shaped turning at the bottom when writing the theta.

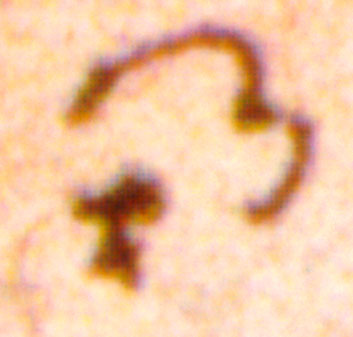

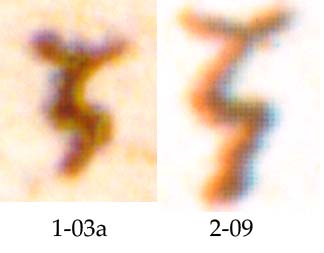

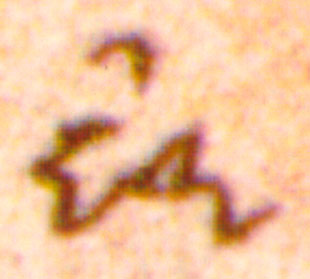

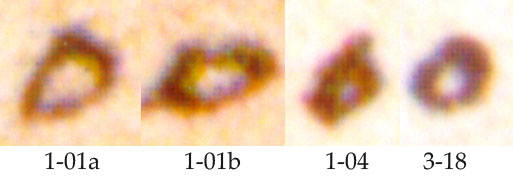

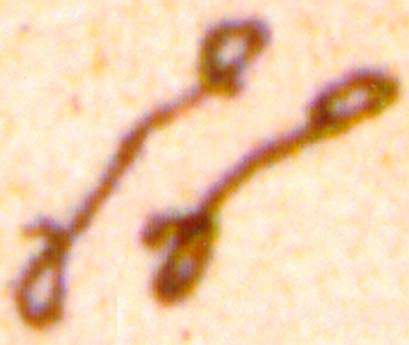

6.2 The square-like omicrons

These omicrons resemble 1-04, and the last example 3-18a is the one also put forward by Carlson. The scribe often used very small omicrons, several of these have a diameter of less than 1 mm in reality, and when they were narrow they sometimes turned into blobs. Further, the omicron 1-01b is really not shaped as a square, but done as illustrated in the image below. I have manipulated the second and third images, in order to show how the omicron was done.

The scribe often wrote the omicron separately, even when it looks like it was connected, as can be demonstrated. In the table below, with omicrons picked from page 3, the first three omicrons are examples of the scribe’s habit of writing omicrons separately and then beginning the stroke at the top and ending it also at the top. Sometimes the lines aligned, sometimes they did not.

The next three examples shows that sometimes, even when the omicron is connected to the previous letter, the scribe all the same wrote it separately. He just connected it to the preceding letter by starting at the top and hopefully meeting the line before making a full turn. In 3-01 we have an example of an open omicron which began at the top and ended just above the starting point; a letter which very much resembles Carlson’s example 1-01b, the one illustrated by my drawing. The connecting line is also visible inside the omicron in 3-01 as it is passing through it. This is even more obvious in 3-11d, where the connecting line passes through the entire omicron and ends above it. The omicron is accordingly connected down the line.

6.3 The long line connecting the omicron-upsilon ligature and the circumflex accent in τοῦ

“The tremor is also apparent in the long lines connecting the omicron-upsilon ligature and the circumflex accent in both the first and the second τοῦ”.

For clarity, I have made an image where I have put the two strokes next to each

other. The first stroke, the one to the left, is previously dealt with regarding

pen lifts in 3.2 The stroke between the omicron-upsilon ligature and the

circumflex accent in

τοῦ,

and the second stroke is the one to the right. In 3.2 also a lot of other

examples were presented, and they clearly show that this scribed normally made

curves when connecting the omicron-upsilon ligature to the circumflex

accent. I therefore give no further examples here.

6.4 The lambda in κλήμεντος

Carlson finds tremor “in the lambda in κλήμεντος”. I have taken the liberty to edit the lambda in Κλήμεντος, by erasing those parts of the tall tau from the line beneath which were intersecting with the lambda. What I find is an exquisitely well drawn one stroke lambda with no apparent tremors and in fact being much smoother than the examples presented in 4.2 The lambda of δοῦλοι.

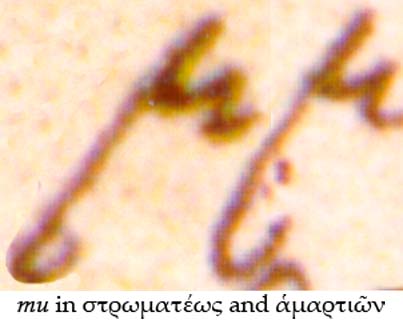

6.5 The mus in Στρωματέως and ἁμαρτιῶν

There is also a small collection of mus to compare these two mus with in 2.11 The mus in μνημεῖον.

Carlson further claims that the “forger’s tremor is manifest in the delta of the word (ὁ-) δοῦ” in line 4 on page 1 (δο presented to the right). In the table below I have collected all combinations of delta-omicron (δο) in the manuscript. The first two lines are those delta-omicrons that are not followed by an upsilon, whereas the last line is where the delta-omicrons are followed by an upsilon and therefore a ligature is used for the omicron-upsilon combination.

Although no real conclusion can be made from these examples, there are obviously other deltas which are at least as “shaky” as the one in Carlson’s example. The foremost example is 3-08 (in page 3 where according to Carlson the writing is more fluid), which also have large ink blobs.

6.7 The lines connecting the alpha and the smooth breathing of ἀπέρατον and ἄβυσσον

“in the lines connecting the alpha and the smooth breathing of ἀπέρατον and ἄβυσσον”.

Both of these are from line 4 on page 1 and presented to the right. There are as far as I can see 13 more alphas in the document, where an alpha with a smooth breathing is written in a similar way, mainly when followed by a pi. They are presented in the table below. For further clarification, see 5.4 Evaluation of the inconsistencies and for an image of higher resolution, click here.

I am not sure where Carlson has registered the tremors, but as far as I can tell, the lines connecting the alpha and the smooth breathing in these 13 examples from page 3, show at least as much tremor as can be seen in the two examples given by Carlson.

6.8 The rhos

Carlson also gives a few examples of tremors in the letter rho. He sees them on page 1 in line 4 in “the rho of ἀπέρατον”, in the “rho in ἁμαρτιῶν” and also in line 7 in the “rho of ἐλευθέρους”. The three rhos are pasted together in the image to the right. The first rho, 1-04a, is the same rho that was examined for a pen lift in 3.4 The middle of the rho of ἀπέρατον. A number of other similar rhos, those preceded by an epsilon and among them also 1-07a, were also presented there in a table and as shown do not in any particular way differ from the examples presented here. The exception seems to be 1-04c which seems to have been connected by a vertical stroke, which then made an almost 90 degrees turn upwards. However, a careful study shows that the rho might have been written separately as seems to be the case also in the second rho in προπαρεσκεύασεν in line 27 on page 1 presented below.

In both of these cases the vertical line in the beginning of the rho appears to begin slightly above the connecting line from the preceding letter and the rho therefore could have been written separately, as is done many times; here are some examples:

6.9 The beta of ἄβυσσον

Carlson does spot tremors in “the beta of ἄβυσσον”, also in line 4 on page 1. What clearly can be seen, are irregularities throughout the entire letter. The question is what they are due to.

There are a total of only 15 betas in the manuscript and I have collected the remaining 14 in the table below. Click here for an image in higher resolution.

Although nothing can be said with certainty, the betas are very consistently written. They all look fairly similar, and that includes also the one put forward by Carlson. Furthermore, I see no big tremor in any of these 15 betas, apart from maybe the turning at the bottom in 3-12. However, the lines are a little shaky, but the question is whether that is because the scribe’s hand was trembling or because of irregularities in the paper which could have absorbed the ink unevenly. These irregularities are visible in for instance 3-10.

One should also remember that the text actually is very small and one can get fooled when enlarging it as much as is done in this article, and thereby irregularities which are not visible by the naked eye becomes much more obvious. The two short taus in 2.3 are in reality no more than 1.3 and 1.4 mm high, the four “square-like” omicrons in 6.2 are only about 1 mm high (between 0.8 mm and 1.0 mm) and even the “large” beta in this example is no more than 2.5 mm high. Viewed on the screen, depending on its size and resolution, the letters will appear to be approximately 25 times as tall and cover a square area of more than 600 times in size compared to their original size on the end paper of the book. This means in reality that the ink blobs and the deviation at the tremors would look 25 times smaller when viewed directly.[3]

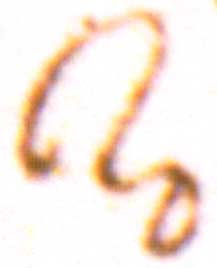

I wrote my own signature in approximately the same size as the Mar Saba Letter was written in, using a rather narrow sized pen, and then scanned and enlarged it. I wrote it rather quick like I do when taking my own notes but in a much smaller size compared to what I normally do. Here is the result enlarged.

In the first place, it is obvious that my pen, although giving fairly thin lines, all the same gave much thicker lines than the ones in the manuscript. Secondly, the letter “o” appears to be square-like and the tremors can be spotted in the letters “n” and “d” at the end. Thirdly, the capital letter V has blunt ends both at the beginning and at the end. There are for sure no ink blobs, but then I did not use a quill pen, dipped in an inkpot.

6.10 The first four letters of δοῦλοι

The next letters to investigate are “the first four letters of δοῦλοι” which all according to Carlson has tremors. The lambda in δοῦλοι was compared for pen lifts in 3.6 The left leg of the lambda in δοῦλοι and for retouching in 4.2 The lambda of δοῦλοι, and the examples of one stroke lambdas presented in 4.2 can be utilized to show that this lambda does not differ in any particular way from other lambdas.

The initial delta was examined in 6.6 The delta in (ὁ-) δοῦ, where also this example was part of the comparison material, and it was clear that other deltas were at least as “shaky” as this one.

They basically all show the same way of writing the omicron-upsilon ligature.

6.11 Both gammas of γεγόνασιν

In line 7 on page 1, Carlson finds the tremor to still be present “in both gammas of γεγόνασιν”. The γεγ at the beginning of the word is presented to the right.

The connection between the epsilon and gamma has previously in 3.7 Between the epsilon and gamma of γεγόνασιν been examined for pen lifts, and the result was that there does not seem to be any pen lift. There are a total of 72 gammas in the manuscript and I settle for showing the 14 from page 3. For a table in higher resolution, click here.

The two gammas from line 7 on page 1 does not appear any shakier than the 14 gammas from page 3. The thicker line on the second gamma looks much like the gamma in 3-08.

6.12 The iota of ἐκεῖ

The final example in this study comes from line 18 on page 2 where Carlson writes that “the forger’s tremor is till evident in the iota of ἐκεῖ”, where κεῖ is presented to the right.

The word ἐκεῖ is found in five places and the endings (κεῖ) of the remaining four is presented below.

If there are tremors in Carlson’s example, then there are tremors also in the other four instances of ἐκεῖ.

6.13 Summary of the tremors

There are for sure irregularities in the text, what Carlson sees as shakiness due to a forger’s slow imitation of a swift cursive hand. However, in the material the so called tremors seem to appear as frequently in the end as in the beginning. This contradicts Carlson’s assertion that the tremors were more frequent in the beginning. Though it should be noticed that neither Carlson nor I has defined what a tremor actually looks like and what parameters should be used to decide whether there is a tremor or not in a particular letter.

Further, one should be aware that the text is very small and written with a very narrow quill pen. This means that very small irregularities become rather big when enlarged as much as is done in this article.

Another explanation of why there are tremors in the manuscript is given by Jack Kilmon. He suggests “that a monk at Mar Saba noticed that the original, a very ancient copy … was so deteriorated that the manuscript was in danger of being lost forever.”[4] He believes that the text which the monk copied was written in an uncial Greek and has reconstructed the original here as it might have looked. This the monk then copied into “a Phanariot Greek minuscule with all of the flourishes and ligatures peculiar to the eighteenth century”.[5] “In a legitimate copy of the original, a ’tremor’ can form where the copyist pauses to check back to the exemplar and there may be an occasional pen rest.”[6] This could also explain some of the ink blobs occurring in places where they normally should not have occurred.

Stephen Carlson’s thesis is that the Letter to Theodoros (the Mar Saba Letter) was in fact written by Morton Smith in the 1950s, imitating a Greek eighteenth century hurried cursive handwriting, but was in reality written very slowly. Carlson implies that the deceiver revealed himself by making more obvious errors in the beginning and improving his ability over time. The examples presented in this article show of no improvement, but rather a consistent way of writing. Despite a few examples of some letters being written in varying ways, the writing is on the whole rather consistent and the scribe manages to consequently write certain letter in different ways but almost always in the same way when following or attaching to certain letters. The examples of pen lifts given by Carlson are sometimes obviously not mistakes but letters meant to be written apart, and the other examples cannot for certain be shown to be pen lifts. Also the three examples Carlson has given for retouching are uncertain and in no way can be seen as proofs of anything. The obvious retouching that has been made a few times is all due to mistakes that the scribe corrected and which he did not try to disguise.

There are blunt ends and ink blobs in the manuscript and there are also many letters which appear to be shaky. They seem to occur as frequent in the end as in the beginning and many can surely be accounted for by peculiarities in the scribe’s way of writing. The cause for the rest cannot be established in this examination, but could at least partly be explained by the very tiny writing with a narrow quill pen. If it can be shown that no other Greek eighteenth century cursive handwriting written with very tiny letters have ink blobs and tremors, then that is a sign of this letter probably being a forgery. However, this has to be accomplished in future studies. For now, others more competent than me, will have access to and be able to examine the presented material themselves and perhaps can give a verdict.

I would also like to point out that it cannot really be both ways. The forger manages to stop in the middle of writing a letter or when combining letters, and to start anew on the same line leaving no traces of this action apart from slightly darker and wider areas. Furthermore he is able to go back and retouch previous mistakes and this time with such accuracy that the signs thereof are minimal; actually so minimal that it is impossible to say whether they are due to retouching or something else. And at the same time the forger’s hand are so shaky, that many letters in the document shows sign of “tremors”. A person whose hands are not shaky, normally a person who is not old, would probably not produce such shaky letters even if he was writing slowly. I therefore suggest that the scribe was an elderly person writing in the eighteenth century.

Copyright © 2009 Roger Viklund 7 February 2009

[1] Chapter 3, "The Modernity of the Mar Saba Manuscript". [2] My thanks go to Scott G. Brown for very generously providing me with the images of the Mar Saba Letter and to Charles Hedrick for giving me the permission to publish the letters for comparison. [3] The book is said to be 20 cm in height http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/1537487?lookfor=&offset=&max=34 and from the fact that my images of the pages are 12 000, 12 200 and 12 300 dots high, I have calculated the height of the letters. [5] Posted on The Jesus Mysteries list on October 9, 2006. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/JesusMysteries/message/27700 [6] Posted on The Jesus Mysteries list on February 28, 2008. http://groups.yahoo.com/group/JesusMysteries/message/36417

|

complete stop at the ends of the strokes.”

complete stop at the ends of the strokes.”

tau

always is written. I have erased the edges of the tau in order to

reproduce it as I think it might have been done and this letter is presented

above to the left.

tau

always is written. I have erased the edges of the tau in order to

reproduce it as I think it might have been done and this letter is presented

above to the left.  vertical

line a little more to the right and

vertical

line a little more to the right and

ending below the

horizontal hook. This could be traces of

ending below the

horizontal hook. This could be traces of “Overall,

in Theodore the scribe shows a marked preference for a tall tau …

except in the word

“Overall,

in Theodore the scribe shows a marked preference for a tall tau …

except in the word

Next

we turn to

Next

we turn to

The

last ink blob Carlson refers to from line 26 on page 2 is “at the beginning of

the letter kappa in

The

last ink blob Carlson refers to from line 26 on page 2 is “at the beginning of

the letter kappa in

indicates that the writing here is a constructed imitation of a cursive hand,

because a cursive writer would accomplish it in a single stroke.”

indicates that the writing here is a constructed imitation of a cursive hand,

because a cursive writer would accomplish it in a single stroke.”

Carlson

continues:

Carlson

continues:

Carlson

also notices another pen lift on “the stroke connecting the epsilon and

the nu in the word

Carlson

also notices another pen lift on “the stroke connecting the epsilon and

the nu in the word

Carlson finds another pen lift “between the epsilon and gamma of

Carlson finds another pen lift “between the epsilon and gamma of

The

final example of a pen lift that Carlson gives, is the word

The

final example of a pen lift that Carlson gives, is the word

was

not connected to the preceding

was

not connected to the preceding

”In

the first line of Theodore … [t]wo of the omicrons, in

”In

the first line of Theodore … [t]wo of the omicrons, in

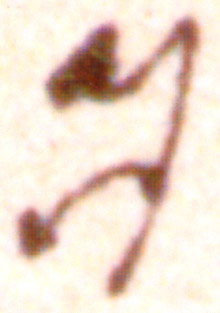

Finally in line 1, Carlson sees a tremor “in the mu in

Finally in line 1, Carlson sees a tremor “in the mu in

The

forger’s tremor is according to Carlson manifest also

The

forger’s tremor is according to Carlson manifest also

The

omicron-upsilon ligature was inspected for ink blobs in

The

omicron-upsilon ligature was inspected for ink blobs in