Tremors, or Just an Optical Illusion?

A Further Evaluation of Carlson’s Handwriting Analysis

by

Roger Viklund

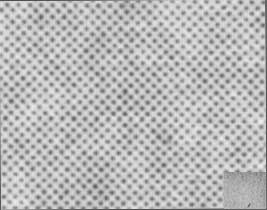

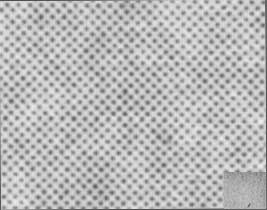

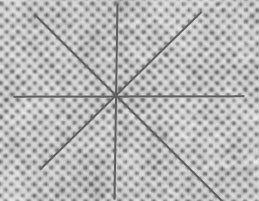

A 45 degrees line screen

I am

now fairly certain why Stephen C. Carlson saw all signs of forgery in the handwriting of

Clement's letter to Theodoros.

It seems all to be due to the basis of his work; printed low resolution

images from Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark by

Morton Smith.

In 2005 Stephen C. Carlson came out with

The Gospel Hoax: Morton

Smith’s invention of Secret Mark. As the title says, Carlson argued

that Morton Smith in fact invented

Clement's letter to Theodoros containing extracts from a

so-called Secret Gospel of Mark. Among the several indications

for this presented by Carlson, he also pointed to the actual writing. We

only have photographs of a now lost copy of the letter. This shows a

text that appears to be written in a hurried cursive eighteenth century

Greek handwriting. Carlson thinks that “it should be possible to tell if the

hurried handwriting of Theodore is natural or simulated.” (Carlson p.

27) He suspects that if Morton Smith forged that handwriting in the

twentieth century, imitating a hurried cursive eighteenth century

handwriting, he would have had to write much more slowly in order to

form the letters in a way which was not typical for his own way of

writing. This careful imitation where the letters are almost drawn

would, according to Carlson, lead to a number of characteristics which

could reveal the counterfeiter (and according to Carlson, this

counterfeiter, or hoaxer, was Morton Smith).

Carlson also claims to have found signs revealing this slow imitating.

He refers to a number of “[b]lunt ends at the beginnings and ends of the

lines” of the letters. This would be the effect of a very slow shaping

of the letters and that the pen thereby came to a stop and the ink would

accumulate. He also finds many instances where the pen was lifted in the

middle of a stroke and this would indicate that Smith needed to prepare

himself for writing the next letter before continuing. Occasionally

Smith still had to go back and retouch certain letters. Further Carlson

sees a lot of tremors in the writing, tremors which reasonably would not

occur if a skilled scribe would have written the letter in a fast pace.

Accordingly the tremors are also an effect of slow writing.

When I previously evaluated Carlson’s claims in the article

Reclaiming Clement's Letter to Theodoros – An Examination of Carlson’s

Handwriting Analysis, I had a tough job in extracting all the

letters for comparison. When I later systemized them and then also could

evaluate Carlson’s assertions, I was often surprised to see that I could not

find the signs that he referred to. I realize now, that I sought to find

them in places where they were not. What I did not do, and of course

should have done, was to compare my colour images, which were scanned in

1200 dpi directly from the colour photos taken by Kallistos Dourvas in

the late 70s, to the images Carlson used, which he took from the printed

images in Morton Smith’s book showing the black and white (b/w) photos

Smith took in 1958. I did at that time however, not have access to

Morton Smith’s Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark.

Now that I have got hold of the book, and have scanned also these

images in 1200 dpi, I realise that the low resolution prints, done on a

printing press in the early 70s, have a line screen at a 45 degrees

angle. I had of course noticed this before and I had also previously

been updated by Scott G. Brown, who informed me of this in an e-mail.

Further, also

Walter

M. Shandruk in a blog post named

Carlson’s Handwriting Analysis on Secret Mark,

noticed how

pixelated the letters were. But the images he presents do not seem to

fully show all the details.

A line screen can be described as

lines

made out of separate dots of different sizes, yet organised in straight lines separated by the

same distance and reproduced at a fixed angle. In this case the angle is

45 degrees. As can be seen from the enlarged image to the right, which

is scanned from the printed black and white images of the letter

found

in Smith’s book, the dots are arranged very symmetric. When you are

printing, as in this case in black and white, there is only one colour,

and that colour is black. There will either be a black dot, or nothing

at all, just the background colour of the paper, which normally is

whitish. If you wish to produce different shades of grey, you still only

have black dots at your disposal. You

fool the eye into believing that the image is grey when viewed at a

normal viewing distance, by letting white and black areas interact with

each other. The more black dots or the larger the dots are, the darker the area

appears to be, and of course, the fewer black dots, the lighter the area

appears. The area to the right is simply a grey background area of the

letter enlarged so that the dots can be seen by the naked eye. In normal magnification the area will appear just grey, as is illustrated

by the same magnified area reduces into the small grey rectangle in the lower

right corner of the image.

found

in Smith’s book, the dots are arranged very symmetric. When you are

printing, as in this case in black and white, there is only one colour,

and that colour is black. There will either be a black dot, or nothing

at all, just the background colour of the paper, which normally is

whitish. If you wish to produce different shades of grey, you still only

have black dots at your disposal. You

fool the eye into believing that the image is grey when viewed at a

normal viewing distance, by letting white and black areas interact with

each other. The more black dots or the larger the dots are, the darker the area

appears to be, and of course, the fewer black dots, the lighter the area

appears. The area to the right is simply a grey background area of the

letter enlarged so that the dots can be seen by the naked eye. In normal magnification the area will appear just grey, as is illustrated

by the same magnified area reduces into the small grey rectangle in the lower

right corner of the image.

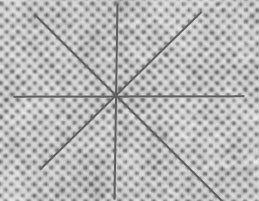

When you print for instance letters, these letters are also made up of

similar dots. However, because of the low resolution reproductions in the book,

the letters will not appear smooth in high magnification. This is due

to the

low resolution line screen. When you enlarge a halftone image very much,

like the one printed in

Smith's

book, you will not see an accurate representation of lines that are not

both perfectly straight and at an angle that accords with the screen. Since the dots are arranged in straight lines

with the same distance between them, you can produce straight lines only

horizontally, vertically or at 45/135 degrees angles (as the screen in

this case is in 45 degrees angle). This

is illustrated in the figure to the right. Whenever you reproduce a line

at a different angle, it will appear stepped and this could

easily be mistaken for a hesitation in drawing the letter. Since

Carlson must have looked at images similar to the ones I shall reproduce

below, I claim that the reason he saw all these signs of forgery is not

due to the fact that there are any such signs, but due the poor images

he used, in which the letters appear to be stepped, but in reality are

not.

Smith's

book, you will not see an accurate representation of lines that are not

both perfectly straight and at an angle that accords with the screen. Since the dots are arranged in straight lines

with the same distance between them, you can produce straight lines only

horizontally, vertically or at 45/135 degrees angles (as the screen in

this case is in 45 degrees angle). This

is illustrated in the figure to the right. Whenever you reproduce a line

at a different angle, it will appear stepped and this could

easily be mistaken for a hesitation in drawing the letter. Since

Carlson must have looked at images similar to the ones I shall reproduce

below, I claim that the reason he saw all these signs of forgery is not

due to the fact that there are any such signs, but due the poor images

he used, in which the letters appear to be stepped, but in reality are

not.

I will not, like I did in my previous article, make a full survey of all

the examples Carlson refers to. I will settle for including about half

of his examples, showing the most obvious

within each category, in order to

demonstrate

how and why Carlson saw

what he saw.

Nor will I refer

to from where the letters are taken, since this information is given in

my previous article

Reclaiming Clement's Letter to Theodoros – An Examination of Carlson’s

Handwriting Analysis. Those who wish to know this will have

to go there.

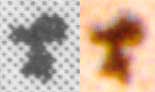

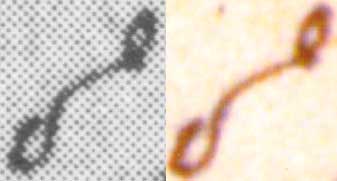

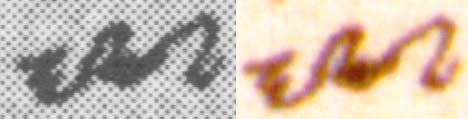

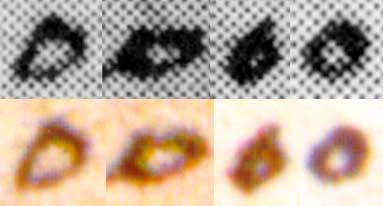

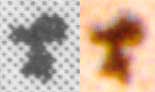

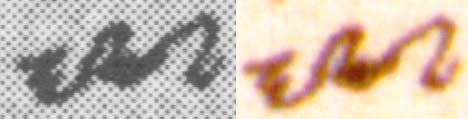

Ink blobs as a result of pen stops

Carlson

sees “blunt

ends at the beginnings and ends of the lines”. This he

says indicates “that the strokes were written so slowly that the pen had

come to a complete stop at the ends of the strokes.” The black and white

images I present here, reasonably represent what Carlson saw. To the

right there is the sign of the cross, which in the b/w image has a

massive ending at the bottom, while the colour image shows fading colour

at the ends.

When these low resolution b/w images are magnified to this size the

shading at the ends of the letters cannot be shown, as they are

constructed of just a few large dots.

All

shades between black and white are missing.

Carlson

sees “blunt

ends at the beginnings and ends of the lines”. This he

says indicates “that the strokes were written so slowly that the pen had

come to a complete stop at the ends of the strokes.” The black and white

images I present here, reasonably represent what Carlson saw. To the

right there is the sign of the cross, which in the b/w image has a

massive ending at the bottom, while the colour image shows fading colour

at the ends.

When these low resolution b/w images are magnified to this size the

shading at the ends of the letters cannot be shown, as they are

constructed of just a few large dots.

All

shades between black and white are missing.

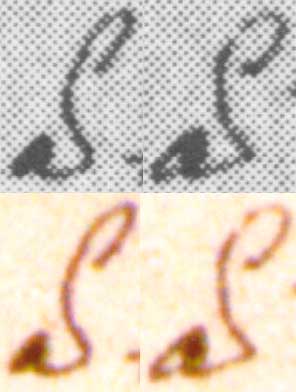

Next

is this tau. Also this time the faded endings cannot be reproduced

in the b/w image, leading to a large blob at the bottom, when in fact

there are two intersecting lines seen in the colour image. The blob that Carlson sees below the

top loop in this tau is also a consequence of the halftone

process.

Next

is this tau. Also this time the faded endings cannot be reproduced

in the b/w image, leading to a large blob at the bottom, when in fact

there are two intersecting lines seen in the colour image. The blob that Carlson sees below the

top loop in this tau is also a consequence of the halftone

process.

After

that

we come to this iota, where we in the colour image can see that

there is a hook upwards to the left, while the b/w image only shows a

big blob. This is in all likelihood the

“ink blob“

that Carlson saw.

The circles below show the ending enlarged and how impossible it is to

render small details with a faded surrounding in the b/w images which

Carlson used.

After

that

we come to this iota, where we in the colour image can see that

there is a hook upwards to the left, while the b/w image only shows a

big blob. This is in all likelihood the

“ink blob“

that Carlson saw.

The circles below show the ending enlarged and how impossible it is to

render small details with a faded surrounding in the b/w images which

Carlson used.

Carlson

finds another

ink blob betraying hesitation at the beginning of this upsilon.

That is at the beginning of the letter down to the left.

Looking at

the colour image, this letter do seems quite ugly, an example of poor

penmanship which could be mistaken as a sign of forgery. The line

thickness at the beginning of this stroke looks though more regular in

the colour image than in the b/w one.

Carlson

finds another

ink blob betraying hesitation at the beginning of this upsilon.

That is at the beginning of the letter down to the left.

Looking at

the colour image, this letter do seems quite ugly, an example of poor

penmanship which could be mistaken as a sign of forgery. The line

thickness at the beginning of this stroke looks though more regular in

the colour image than in the b/w one.

Finally

we have this sigma where the “ink blobs” look more prominent in the

b/w image than they do in the colour image.

Finally

we have this sigma where the “ink blobs” look more prominent in the

b/w image than they do in the colour image.

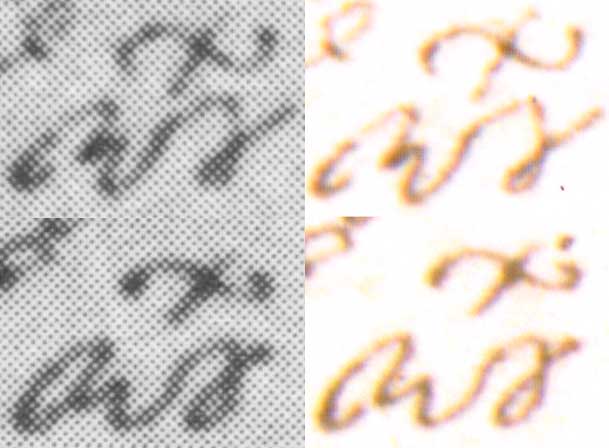

Pen lifts and retakes

Carlson claims that on several occasions, where a skilled

scribe would have written in one stroke, this scribe stops, lifts the

pen and begins anew. I leave aside the example Carlson gives for of a

pen

lift between epsilon and kappa, where there certainly is a

pen lift, but where this scribe always lifts his pen

as he never

connects the letter kappa to the preceding letter. For the rest,

there are obvious

examples

where the 45 degree angle of the screen contorts the line,

creating the illusion of hesitation, retakes, or unnatural shifts in

direction. In for instance this stroke

between the omicron-upsilon ligature and the circumflex accent,

Carlson sees a pen lift. That is on the middle of the long diagonal

line, which also is enlarged in the circle. On the colour image one can

clearly see that this line is drawn in one stroke, yet in a curve which

is a characteristic of this scribe when he writes this letter. However,

in the b/w image the curve appears as if there is a break in the line

and one or two retakes beginning beside/below/above the line. Now, this

is a consequence of the line screen not being able to reproduce the

curve, and instead beginning on another line of dots along the 45

degrees angle, in order to follow the letter’s curve.

where the 45 degree angle of the screen contorts the line,

creating the illusion of hesitation, retakes, or unnatural shifts in

direction. In for instance this stroke

between the omicron-upsilon ligature and the circumflex accent,

Carlson sees a pen lift. That is on the middle of the long diagonal

line, which also is enlarged in the circle. On the colour image one can

clearly see that this line is drawn in one stroke, yet in a curve which

is a characteristic of this scribe when he writes this letter. However,

in the b/w image the curve appears as if there is a break in the line

and one or two retakes beginning beside/below/above the line. Now, this

is a consequence of the line screen not being able to reproduce the

curve, and instead beginning on another line of dots along the 45

degrees angle, in order to follow the letter’s curve.

Another

example where Carlson spots a pen lift, is between this alpha

and this tau. In my

previous study (3.5), I assumed this to be at the connection at the left

top of the

tau,

where

there is a slightly darker area which can be seen in the colour photo,

and as I did not find any other obvious signs of a pen lift. However, in the b/w

image there are signs of a pen lift in the

bottom of the curved line which

is cut out and enlarged into the ellipse below. As the lines of dots

along the 45 degrees angle continues downwards, it actually looks like a

break and a retake at the spot where the arrow points. The same curve appears to be smooth and written in one stroke

in the colour image. The bend is however impossible to reproduce smooth in the b/w

image and therefore it looks like the scribe stopped and then began a

little further to the right.

Another

example where Carlson spots a pen lift, is between this alpha

and this tau. In my

previous study (3.5), I assumed this to be at the connection at the left

top of the

tau,

where

there is a slightly darker area which can be seen in the colour photo,

and as I did not find any other obvious signs of a pen lift. However, in the b/w

image there are signs of a pen lift in the

bottom of the curved line which

is cut out and enlarged into the ellipse below. As the lines of dots

along the 45 degrees angle continues downwards, it actually looks like a

break and a retake at the spot where the arrow points. The same curve appears to be smooth and written in one stroke

in the colour image. The bend is however impossible to reproduce smooth in the b/w

image and therefore it looks like the scribe stopped and then began a

little further to the right.

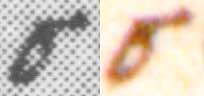

Next

we have this lambda,

where Carlson sees “[u]nnatural pen lifts in the middle of what should

be” a smooth curve in the left leg. This was one of the examples where I

in my previous evaluation was unable to see where Carlson saw the pen

lift. Now I realize that he must have taken the

broken line on the leg down to the

left for a retake, while in reality the appearance is solely due to the fact

that in order to follow the line, which is done in

perhaps a 35 degrees angle (and also

gets narrower and then wider), the dots have to shift position as

they are following the 45 degrees angle. This break can only be seen in

the b/w image, and it is enlarged in the circle for a better view. This

also explains why in my previous study, where I used the same colour

images as presented here, I could not find any retake.

broken line on the leg down to the

left for a retake, while in reality the appearance is solely due to the fact

that in order to follow the line, which is done in

perhaps a 35 degrees angle (and also

gets narrower and then wider), the dots have to shift position as

they are following the 45 degrees angle. This break can only be seen in

the b/w image, and it is enlarged in the circle for a better view. This

also explains why in my previous study, where I used the same colour

images as presented here, I could not find any retake.

All

of these examples show that when lines are produced at angles which

differ markedly from the angles possible to reproduce correctly, the lines will be

stepped and it will appear as if the pen was lifted and a new stroke was

done beginning on a different level. This holds true also for the next

example, where Carlson finds a pen lift between the epsilon and

gamma. The actual place where the break appears, is cut out and

enlarged in this ellipse. It really looks like the epsilon is done separately and

the gamma is connected a little bit above the epsilon. As can be seen in

the enlargement,

the line that begins at the epsilon first follows the 45 degrees

angle of the line screen, then turns left straight upwards in a 90 degree angle

along the vertical line

and the turns right to follow the 45 degrees angle again. The colour image

shows that the real angle is about 60 degrees and that there is no

break.

All

of these examples show that when lines are produced at angles which

differ markedly from the angles possible to reproduce correctly, the lines will be

stepped and it will appear as if the pen was lifted and a new stroke was

done beginning on a different level. This holds true also for the next

example, where Carlson finds a pen lift between the epsilon and

gamma. The actual place where the break appears, is cut out and

enlarged in this ellipse. It really looks like the epsilon is done separately and

the gamma is connected a little bit above the epsilon. As can be seen in

the enlargement,

the line that begins at the epsilon first follows the 45 degrees

angle of the line screen, then turns left straight upwards in a 90 degree angle

along the vertical line

and the turns right to follow the 45 degrees angle again. The colour image

shows that the real angle is about 60 degrees and that there is no

break.

Next

we have a connection between epsilon and pi, or as

Carlson puts it

“between the pi and the epsilon”. Also this

time the line appear stepped in the b/w image. But there is no pen lift

and accordingly no retake.

Next

we have a connection between epsilon and pi, or as

Carlson puts it

“between the pi and the epsilon”. Also this

time the line appear stepped in the b/w image. But there is no pen lift

and accordingly no retake.

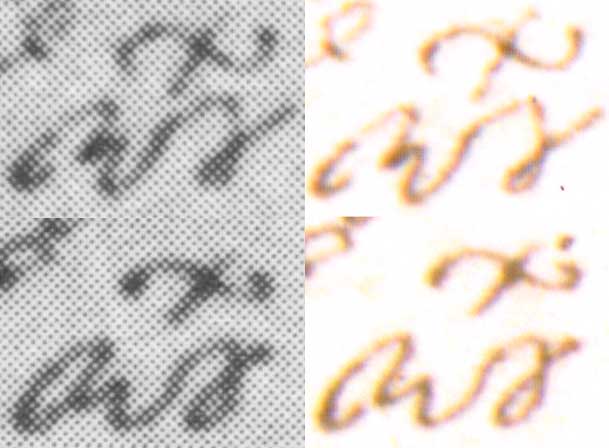

Another

obvious illustration comes from the two examples of the abbreviated κυρίου where,

according to Carlson, there are “pen lifts between the initial kappa

and the final omicron-upsilon ligature”. Right at the centre of both b/w images, where the two letters

are connected, the lines are

stepped. This Carlson must have taken for a pen stop; that the scribe lifted the

pen and began anew a little bit above the stop. As can be seen in the colour images, this is not true

but an effect of the line screen not being able to produce the bend.

Another

obvious illustration comes from the two examples of the abbreviated κυρίου where,

according to Carlson, there are “pen lifts between the initial kappa

and the final omicron-upsilon ligature”. Right at the centre of both b/w images, where the two letters

are connected, the lines are

stepped. This Carlson must have taken for a pen stop; that the scribe lifted the

pen and began anew a little bit above the stop. As can be seen in the colour images, this is not true

but an effect of the line screen not being able to produce the bend.

As Carlson actually gives only three examples of retouching, and these

are closely connected with the pen lifts (one of the examples is the

lambda presented here and which according to Carlson

“shows

a lot of retouching”), I do not give any such example.

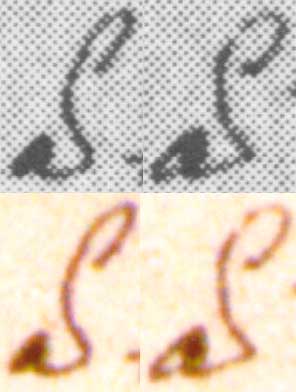

Tremors due to slow writing

Finally

there are the forger’s tremors. Carlson writes: “The

‘forger’s tremor’ appears in the shaky quality of lines that should be

smooth curves.” But

the curves only appear not to be smooth from the low resolution line

screen of Carlson’s images. A good example is this theta, where

especially the lower part looks shaky, while none of this can be seen in

the high resolution colour image. One can see that Carlson’s

claim

that in

“the

first line of Theodore, the shakiness

is evident in the

theta

of

Θεοδώρῳ”

only holds true for the b/w

image.

Finally

there are the forger’s tremors. Carlson writes: “The

‘forger’s tremor’ appears in the shaky quality of lines that should be

smooth curves.” But

the curves only appear not to be smooth from the low resolution line

screen of Carlson’s images. A good example is this theta, where

especially the lower part looks shaky, while none of this can be seen in

the high resolution colour image. One can see that Carlson’s

claim

that in

“the

first line of Theodore, the shakiness

is evident in the

theta

of

Θεοδώρῳ”

only holds true for the b/w

image.

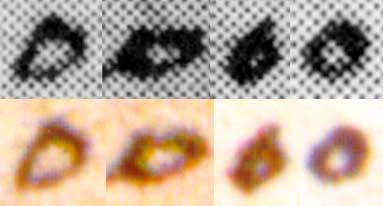

Other

good

examples are the so called squarish

omicrons Carlson spotted. He

claims that they “are so shakily written as to appear square rather than

circular”. All four omicrons which Carlson identified as being square

rather than circular are presented here. One can especially look at the

omicron furthest to the right, which is quite circular in the colour

image, but appears to be a square in the b/w image. The same pair of omicrons are presented also to the left and then magnified even more. This may demonstrate why the b/w images become distorted.

These omicrons are really small. In reality they are only about

1

Other

good

examples are the so called squarish

omicrons Carlson spotted. He

claims that they “are so shakily written as to appear square rather than

circular”. All four omicrons which Carlson identified as being square

rather than circular are presented here. One can especially look at the

omicron furthest to the right, which is quite circular in the colour

image, but appears to be a square in the b/w image. The same pair of omicrons are presented also to the left and then magnified even more. This may demonstrate why the b/w images become distorted.

These omicrons are really small. In reality they are only about

1

mm

in diameter, and the omicron to the right, which is also enlarged

to the left, is c. 0.96 mm wide and c. 0.91 mm high.

When a

small circle

is created with these dots, they are mainly following the

lines

of 45 and 135 degrees angles, forming a square standing

on its corner. If one looks at the inner circle in the centre of the omicron, which obviously is quite round, the b/w image composes of

only four white squares and the surrounding black dots can then only

follow the lines of 45 and 135 degrees angles. The

same holds true also

for the outer circle.

mm

in diameter, and the omicron to the right, which is also enlarged

to the left, is c. 0.96 mm wide and c. 0.91 mm high.

When a

small circle

is created with these dots, they are mainly following the

lines

of 45 and 135 degrees angles, forming a square standing

on its corner. If one looks at the inner circle in the centre of the omicron, which obviously is quite round, the b/w image composes of

only four white squares and the surrounding black dots can then only

follow the lines of 45 and 135 degrees angles. The

same holds true also

for the outer circle.

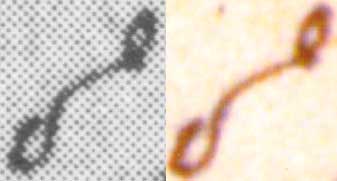

Lines

produced

at angles which are not following the lines of the dots will appear

stepped and could

be mistaken for tremors. The

long line connecting the omicron-upsilon ligature

and the circumflex

to the right, where Carlson

sees a tremor,

is a good example of this.

This tremor can only be seen in the b/w image and is due to

the fact that the line is bending away from 45 degrees to

perhaps 30

degrees.

Lines

produced

at angles which are not following the lines of the dots will appear

stepped and could

be mistaken for tremors. The

long line connecting the omicron-upsilon ligature

and the circumflex

to the right, where Carlson

sees a tremor,

is a good example of this.

This tremor can only be seen in the b/w image and is due to

the fact that the line is bending away from 45 degrees to

perhaps 30

degrees.

The

mu to the right, where Carlson

also sees a tremor,

is another good example. The tremor in the leg of the mu is

prominent in the b/w image compared to the colour

image.

The

mu to the right, where Carlson

also sees a tremor,

is another good example. The tremor in the leg of the mu is

prominent in the b/w image compared to the colour

image.

Also

in these

two examples of

the letter

alpha with a smooth breathing, Carlson see tremors in the line which connects the

alpha and the

smooth breathing. It seems obvious that the stepped lines in the b/w image could be

mistaken for tremors.

Also

in these

two examples of

the letter

alpha with a smooth breathing, Carlson see tremors in the line which connects the

alpha and the

smooth breathing. It seems obvious that the stepped lines in the b/w image could be

mistaken for tremors.

Carlson

gives three

examples of tremors in the letter rho,

and I am reproducing just one of them. Also this time the letter does

appear to be shaky in the b/w image, while none of this is

visible

in the colour image.

Carlson

gives three

examples of tremors in the letter rho,

and I am reproducing just one of them. Also this time the letter does

appear to be shaky in the b/w image, while none of this is

visible

in the colour image.

No basis for

judgement

This somewhat short survey still demonstrates that Carlson’s assertion that the handwriting of

Clement’s letter to Theodoros

shows signs of ink blobs, pen lifts, retouches and tremors, cannot withhold a

critical examination. These signs lie rather in the poor images Carlson

used than in the writing itself. The signs of forgery which Carlson

claims could be detected in the handwriting

cannot

really be used as a

basis for judgement of the letter’s authenticity, since the

quality of the images he used

is

simply too poor. On the contrary, it

can be said that the high resolution colour images do not show any

conspicuously marks of

ink blobs, pen lifts, retouches and tremors; thereby strengthening the

opinion that the text was indeed written rather swiftly. This does in

turn strengthen the opinion that the text was written by a skilled

scribe in the eighteenth century.

Copyright ©

2009

Roger Viklund

12 December

2009

found

in Smith’s book, the dots are arranged very symmetric. When you are

printing, as in this case in black and white, there is only one colour,

and that colour is black. There will either be a black dot, or nothing

at all, just the background colour of the paper, which normally is

whitish. If you wish to produce different shades of grey, you still only

have black dots at your disp

found

in Smith’s book, the dots are arranged very symmetric. When you are

printing, as in this case in black and white, there is only one colour,

and that colour is black. There will either be a black dot, or nothing

at all, just the background colour of the paper, which normally is

whitish. If you wish to produce different shades of grey, you still only

have black dots at your disp Smit

Smit

Next

is this tau. Also this time the faded endings cannot be reproduced

in the b/w image, leading to a large blob at the bottom, when in fact

there are two intersecting lines seen in the colour image. The blob that Carlson sees below the

top loop in this tau is also a consequence of the halftone

process.

Next

is this tau. Also this time the faded endings cannot be reproduced

in the b/w image, leading to a large blob at the bottom, when in fact

there are two intersecting lines seen in the colour image. The blob that Carlson sees below the

top loop in this tau is also a consequence of the halftone

process. After

that

After

that

Another

example where Carlson spots a pen lift, is between this alpha

and this tau. In my

Another

example where Carlson spots a pen lift, is between this alpha

and this tau. In my

All

of these examples show that when lines are produced at angles which

differ markedly from the angles possible to reproduce correctly, the lines will be

stepped and it will appear as if the pen was lifted and a new stroke was

done beginning on a different level. This holds true also for the next

example, where Carlson finds a pen lift between the epsilon and

gamma. The actual place where the break appears, is cut out and

enlarged in this ellipse. It really looks like the epsilon is do

All

of these examples show that when lines are produced at angles which

differ markedly from the angles possible to reproduce correctly, the lines will be

stepped and it will appear as if the pen was lifted and a new stroke was

done beginning on a different level. This holds true also for the next

example, where Carlson finds a pen lift between the epsilon and

gamma. The actual place where the break appears, is cut out and

enlarged in this ellipse. It really looks like the epsilon is do Next

we have a connection between epsilon and pi, or as

Carlson puts it

Next

we have a connection between epsilon and pi, or as

Carlson puts it  Another

Another

Finally

there are the forger’s tremors. Carlson writes: “

Finally

there are the forger’s tremors. Carlson writes: “ Other

good

Other

good

The

The Also

in th

Also

in th